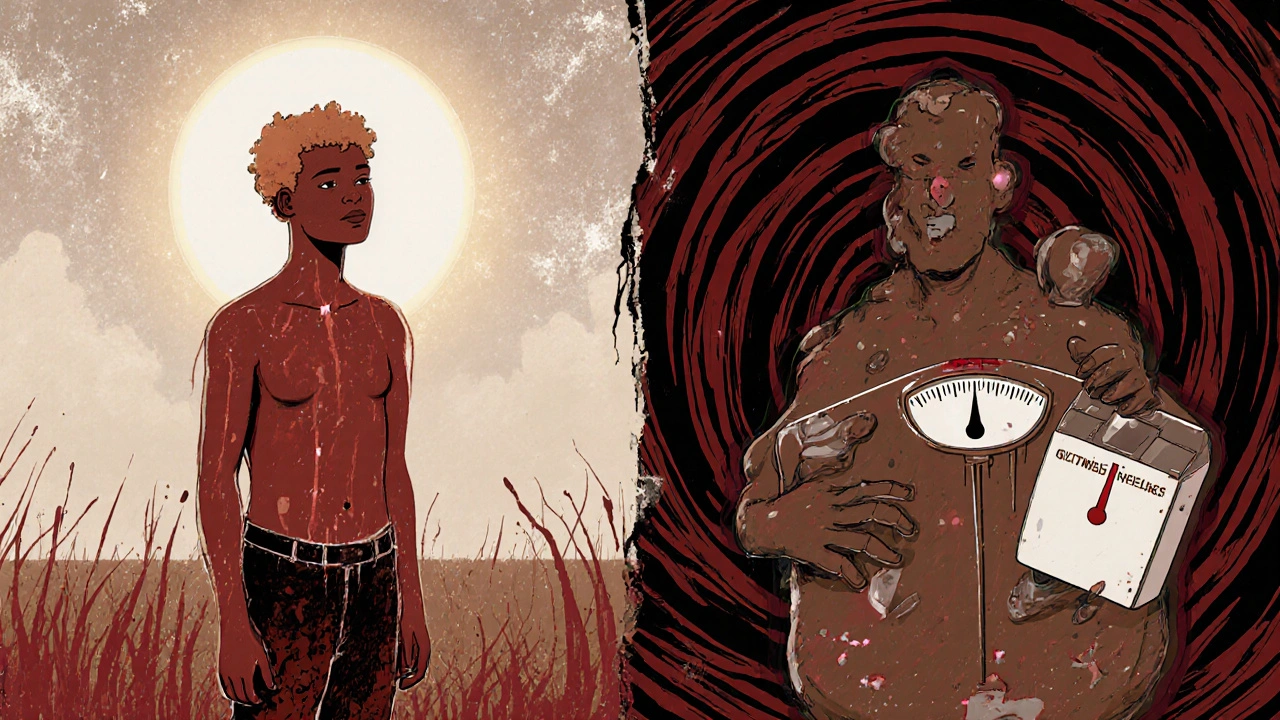

Managing bipolar disorder isn’t about finding one magic pill. It’s about balancing effectiveness with tolerability-because the meds that help your moods can also change your body in ways you didn’t expect. For many people, the journey starts with lithium or quetiapine, but the real challenge isn’t just taking them. It’s sticking with them when the side effects hit hard.

Why Mood Stabilizers Are Still the Foundation

Lithium has been the go-to treatment for bipolar disorder since the 1970s, and for good reason. It doesn’t just calm mania-it lowers the risk of suicide by 80% compared to not taking anything at all. That’s not a small number. It’s life-saving. But lithium isn’t simple. You need regular blood tests to make sure your levels stay between 0.6 and 1.0 mmol/L. Too low, and it won’t work. Too high, and you risk toxicity-slurred speech, shaking, even seizures.People on lithium often feel like they’re constantly thirsty. Drinking three liters of water a day isn’t unusual. You’ll pee more, your hands might shake, and you might gain 10 to 15 pounds in the first year. Some switch to valproate or carbamazepine because they don’t want to deal with that. But those have their own risks: liver issues, birth defects if you’re pregnant, or dangerous drug interactions.

Lamotrigine is different. It’s the only mood stabilizer proven to help with depression without triggering mania. About 47% of people see real improvement in their low moods, and weight gain? Minimal. But here’s the catch: 1 in 10 people develop a serious skin rash. It starts mild, like a sunburn, but can turn deadly if ignored. That’s why doctors start you on a tiny dose and increase it slowly-sometimes over weeks.

Antipsychotics: Faster Relief, Heavier Costs

If you’re in the middle of a manic episode, antipsychotics like quetiapine or olanzapine can bring you down faster than lithium. Some people feel better in just seven days. That’s why they’re often used first in crisis situations. But the trade-off is steep.Quetiapine causes drowsiness in 60 to 70% of users. You might need to take it at night just to function during the day. Weight gain is common-on average, people gain 22 pounds over months. Olanzapine is worse: 20 to 30% higher risk of type 2 diabetes, and metabolic changes that show up in blood work within weeks. One patient on PatientsLikeMe said, “I gained 30 pounds in four months. I didn’t eat more. I just felt like my body was storing everything.”

Not all antipsychotics are the same. Newer ones like lurasidone and cariprazine were designed to avoid these problems. In 2023, the Canadian guidelines put them first-line for bipolar depression because they cause less weight gain and don’t spike blood sugar. Lurasidone adds only 0.8kg in six weeks. Quetiapine? 3.5kg. That’s a huge difference when you’re trying to stay healthy long-term.

Combining Meds: When One Isn’t Enough

Many people need more than one medication. A mood stabilizer plus an antipsychotic works for about 70% of those who don’t respond to either alone. But combining them doesn’t double the help-it doubles the side effects. You might get better mood control, but now you’re also dealing with tremors, drowsiness, weight gain, and metabolic issues all at once.Some doctors try to offset the weight gain with metformin, a diabetes drug. It’s not perfect, but it helps. One Reddit user wrote, “I’m on lithium and quetiapine. I gained 40 pounds. My doctor added metformin. I lost 18 in six months. It’s not magic, but it’s something.”

Antidepressants? They’re risky. Even though they work for unipolar depression, in bipolar disorder, they can flip you into mania. About 10 to 15% of people experience this switch. If they’re used at all, they’re always paired with a mood stabilizer. Fluoxetine might help your low mood, but without lithium or valproate, it could cost you your stability.

Monitoring: It’s Not Optional

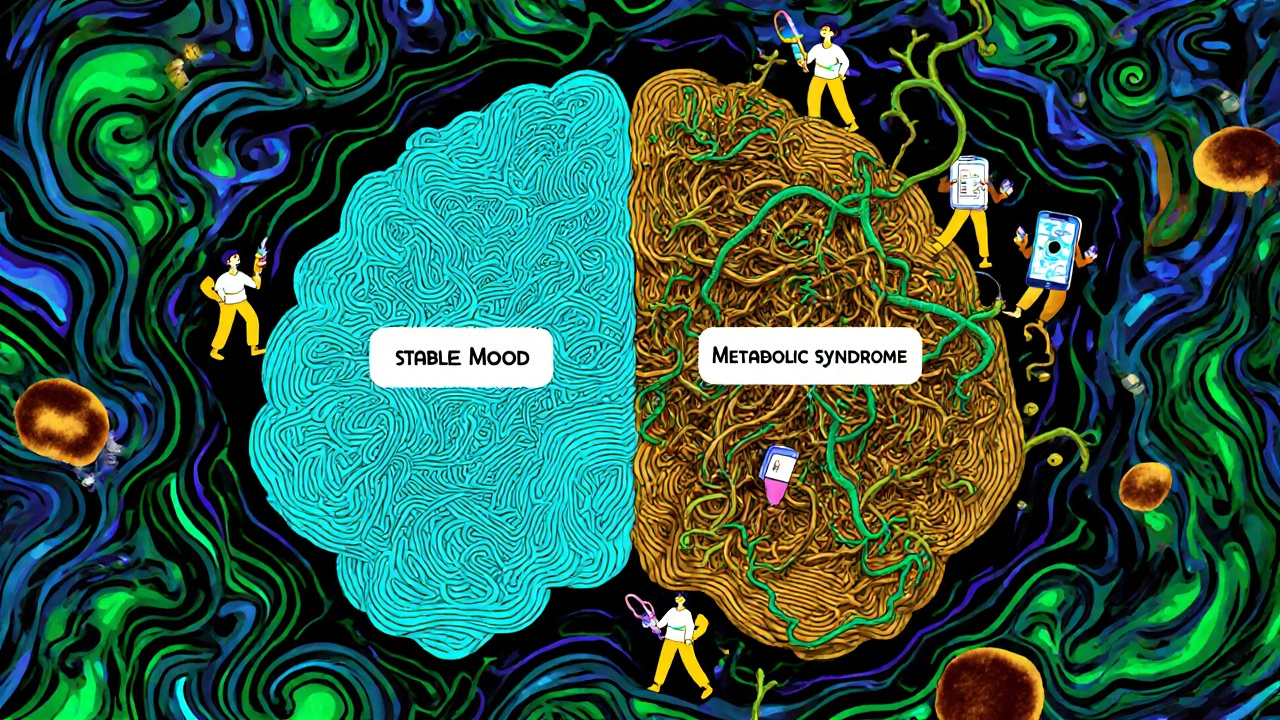

This isn’t a set-it-and-forget-it situation. Blood tests every few months aren’t just paperwork-they’re safety checks. Lithium affects your kidneys and thyroid. Antipsychotics mess with your blood sugar, cholesterol, and waistline. Doctors now recommend checking your BMI, waist size, fasting glucose, and lipids every three months. If you’re on olanzapine or quetiapine, you’re at higher risk for metabolic syndrome. That means a waist over 40 inches for men, 35 for women, plus high blood pressure or sugar.And drug interactions? They’re sneaky. Taking ibuprofen or naproxen with lithium can push your levels into toxic range. Even common antibiotics can interfere. Always tell every doctor you see-dentist, GP, ER-that you’re on bipolar meds. One patient ended up in the hospital after taking a cold medicine that raised his lithium level by 30%.

Real Stories, Real Choices

People’s experiences vary wildly. One person said, “Lithium saved me. I gained weight, I was always thirsty, but I haven’t had a suicidal episode in three years.” Another said, “I tried five meds. Lamotrigine gave me insomnia. Quetiapine made me sleepy and fat. I quit. Now I’m in therapy and using a digital app to track my moods. It’s not perfect, but I’m not on pills anymore.”There’s no one-size-fits-all. What works for someone else might wreck your life. That’s why personalized treatment matters. Genetic tests like Genomind’s can now predict how your body breaks down certain drugs. If you’re a slow metabolizer of CYP2D6, you might get too much of a drug even at low doses. That’s not science fiction-it’s happening now in clinics.

What’s Next? The Future Is Personalized

Long-acting injectables like Abilify Maintena mean you only need a shot once a month. That helps people who struggle with daily pills. New drugs like lumateperone (Caplyta) are showing promise with almost no weight gain. And digital tools like reSET-BD, an app approved by the FDA, help people track mood, sleep, and medication adherence. In trials, users had 22% fewer relapses.But here’s the hard truth: only 35% of people with bipolar disorder ever reach full remission. Six in ten still deal with side effects that make them want to quit. The goal isn’t perfection. It’s balance. Finding the lowest dose that keeps you stable, with the fewest side effects you can live with.

It’s not about being “cured.” It’s about staying alive, staying functional, and staying yourself. And sometimes, that means accepting a little weight gain, a little thirst, or a little drowsiness-for the chance to feel like you’re not falling apart every few weeks.

Can you take mood stabilizers and antipsychotics together?

Yes, many people take both, especially if one type alone isn’t enough. Combining a mood stabilizer like lithium with an antipsychotic like quetiapine can improve response rates to about 70% in treatment-resistant cases. But side effects also increase-weight gain, drowsiness, and metabolic issues become more likely. Doctors usually start with one, then add the other only if needed.

Which medication causes the least weight gain?

Lamotrigine causes the least weight gain among mood stabilizers-most people gain little to no weight. Among antipsychotics, lurasidone and aripiprazole are the best options. Lurasidone adds less than 1kg in six weeks, while quetiapine and olanzapine can cause 3 to 5kg in the same time. If weight is a major concern, these are the first choices.

How often do you need blood tests for lithium?

When you first start lithium, you need blood tests weekly until your dose and levels stabilize. Once you’re on a steady dose, tests drop to every 2 to 3 months. For older adults or those with kidney issues, tests may be more frequent. Levels should stay between 0.6 and 1.0 mmol/L for maintenance, and never exceed 1.2 mmol/L to avoid toxicity.

Why are antidepressants used cautiously in bipolar disorder?

Antidepressants can trigger mania or rapid cycling in people with bipolar disorder. Studies show a 10 to 15% risk of switching into mania, and some experts say it’s even higher. If used, they’re always paired with a mood stabilizer. Many clinicians avoid them entirely, especially if the person has had previous manic switches. Therapy and non-drug approaches are often preferred for depression.

What should you do if you can’t tolerate your medication side effects?

Don’t stop cold turkey. Talk to your psychiatrist. Side effects like weight gain, tremors, or drowsiness can often be managed-switching to a different drug, lowering the dose, or adding a second medication like metformin. Some side effects fade after a few weeks. But if they’re unbearable, there are alternatives. Lamotrigine, lurasidone, or long-acting injectables may be better fits. Your treatment plan should evolve with your needs.

Is there a cure for bipolar disorder?

There’s no cure yet. But with the right combination of medication, therapy, and lifestyle, most people can live stable, fulfilling lives. The goal isn’t to eliminate all mood swings-it’s to reduce their severity and frequency so they don’t take over your life. About 35% of people reach full remission, and many more manage well enough to work, raise families, and stay out of crisis.

Swati Jain

Let me just say - if you’re on quetiapine and gaining weight like it’s your job, you’re not broken. Your metabolism is just being a passive-aggressive roommate. I’ve seen people lose 20 lbs on lurasidone after years of struggling. It’s not magic, but it’s science that actually listens. And yes, the docs will make you jump through hoops to get it - but so what? Your body deserves better than a 30-pound burden you didn’t sign up for. 💪

Simone Wood

Okay but have you considered that maybe the real issue isn’t the meds it’s that no one teaches you how to eat when you’re depressed and then suddenly you’re on a drug that makes you hungry ALL THE TIME and then you’re crying in front of the fridge at 3am wondering why your pants don’t fit anymore and your therapist says ‘just practice mindfulness’ like that’s going to stop your body from turning oatmeal into fat cells??

jim cerqua

They say lithium saves lives - and it does. But they don’t tell you that it also steals your joy in small ways: the morning coffee that tastes like metal, the constant thirst that turns hydration into a chore, the way your hands shake like you’re having a silent seizure every time you reach for your phone. I stayed on it for five years. I didn’t kill myself. But I didn’t really live either. Until I switched. And now? I’m not ‘cured’ - I’m just not drowning. And that’s enough.

David Cusack

Interesting how the article casually mentions lamotrigine’s 1-in-10 rash risk - as if it’s a minor footnote - when in reality, SJS is a death sentence disguised as a breakout. And yet, doctors still push it like it’s a vitamin. Meanwhile, the FDA-approved apps? They’re marketed as ‘digital therapeutics’ - but let’s be real: they’re just corporate placeholders for the fact that we’ve outsourced human care to algorithms that can’t even tell if you’re crying or just scrolling.

Florian Moser

For anyone feeling like giving up on meds - you’re not weak. You’re human. And there are options now that didn’t exist five years ago. Lurasidone, cariprazine, long-acting injectables - they’re not perfect, but they’re better. Talk to your psychiatrist. Bring this article. Ask for genetic testing. You deserve a treatment plan that doesn’t make you feel like a side effect factory. Keep going.

Willie Doherty

The data on metabolic syndrome with olanzapine is unequivocal: 27% increased risk over 12 months, with insulin resistance detectable as early as week 4. Yet, primary care physicians rarely coordinate with psychiatrists to monitor HbA1c, triglycerides, or waist-to-hip ratios. This is a systemic failure - not a patient compliance issue. The burden of monitoring is placed on the individual, while the prescriber remains insulated by inertia and reimbursement structures.

Elaina Cronin

Let me be absolutely clear: if your doctor tells you to ‘just stick with it’ when you’re gaining weight, shaking, and feeling like a zombie - they are not listening. You are not a statistic. You are not a case study. You are a person with a right to dignity, to bodily autonomy, to a life that doesn’t feel like a slow poisoning. If they won’t help you switch - find someone who will. Your life is not negotiable.

Darragh McNulty

Just wanted to say - I was on lithium for 3 years. Gained 35 lbs. Couldn’t sleep. Felt like a ghost. Then I switched to lurasidone + therapy. Lost 20 lbs in 4 months. Started hiking again. Smiled without forcing it. I’m not ‘fixed’ - but I’m here. And that’s worth fighting for. 🙌 You’re not alone. Keep showing up.

Donald Frantz

What about the people who can’t afford these newer meds? Lurasidone costs $1,200/month without insurance. Metformin is $4. Lithium is $10. So we’re supposed to choose between survival and bankruptcy? The system doesn’t care if you live - it cares if you’re cost-efficient. That’s the real diagnosis here.