When you pick up a generic pill at the pharmacy, you expect it to work just like the brand-name version. But how does the FDA make sure it actually does? The answer isn’t in clinical trials on thousands of patients-it’s in a simple lab test called dissolution testing.

What Dissolution Testing Really Means

Dissolution testing measures how quickly a drug releases its active ingredient in a controlled lab environment. Imagine dropping a pill into a liquid that mimics your stomach. The test tracks how much of the drug dissolves over time. If the generic dissolves at the same rate as the brand-name drug, it’s likely to behave the same way in your body. This isn’t just a formality. It’s the core of how the FDA approves generic drugs without running expensive and time-consuming human trials. For most oral solid drugs-tablets and capsules-dissolution data replaces the need for bioequivalence studies in people. The FDA uses it as a reliable predictor of what happens inside your body.How the FDA Sets the Rules

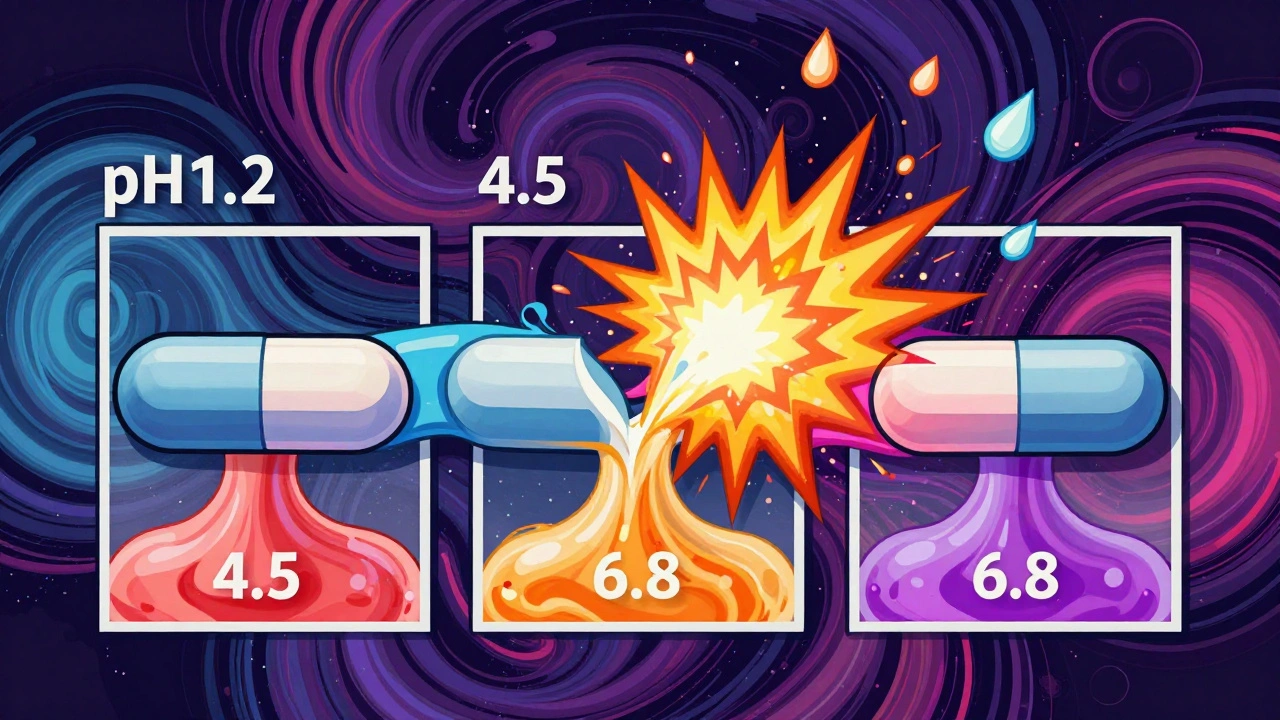

The FDA doesn’t guess at dissolution standards. They build them on science. For every drug, they look at how the original brand-name product behaves. Then they require generics to match that performance exactly. There are five key data points the FDA demands in every generic drug application:- How soluble the active ingredient is in different pH levels

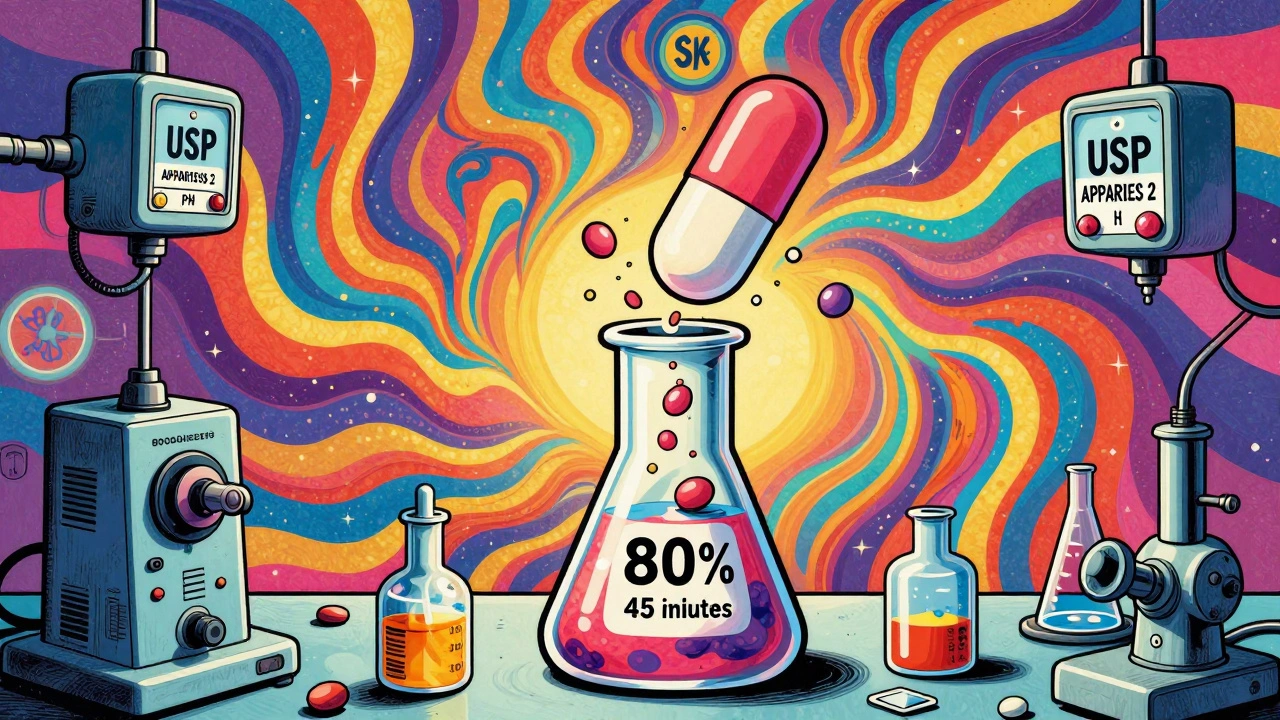

- Exactly how the test is run: what machine (usually USP Apparatus 1 or 2), what speed (50-100 rpm), what liquid (pH 1.2, 4.5, or 6.8 buffers), and how much volume (500-900 mL)

- Proof the test works under slight changes-like if the temperature shifts or the stirring speed varies

- Validation that the lab can accurately measure how much drug is dissolved

- Proof the method can tell the difference between good and bad formulations

Why This Matters for Low-Solubility Drugs

Not all drugs are easy to dissolve. Some, like certain antibiotics or antifungals, are poorly soluble. For these, a simple 80% in 45 minutes rule won’t cut it. A generic version might dissolve 80% but too slowly-or too fast at first-leading to poor absorption. That’s why the FDA requires extra steps for these drugs. Manufacturers must prove their dissolution method can distinguish between formulations that work and those that don’t. A method that can’t tell the difference is useless. If two pills dissolve the same amount but one releases the drug too quickly and causes side effects, the test must catch that. This is where the f2 similarity factor comes in. It’s a statistical tool that compares the dissolution curves of the generic and brand-name drug. An f2 score of 50 or higher means the two profiles are similar enough to be considered equivalent. A score below 50 triggers more questions-and often more testing.

Modified-Release Drugs Are a Whole Different Challenge

Time-release pills are designed to slowly let the drug out over hours. If they release too fast, you get a dangerous spike in blood levels. If they release too slow, you get no effect. For these products, the FDA doesn’t just test in one pH. They test in three: stomach acid (pH 1.2), small intestine (pH 4.5), and colon (pH 6.8). They also test with alcohol-up to 40% ethanol-to simulate what happens if someone drinks while taking the pill. This is called an alcohol challenge test. Why? Because some extended-release formulations can suddenly dump all their drug content when mixed with alcohol. That’s called dose-dumping. It’s led to overdoses and hospitalizations. The FDA’s dissolution tests are designed to catch these risks before the drug even hits the market.What Happens When a Generic Changes?

Manufacturers don’t always use the same factory, ingredients, or process. Maybe they switch suppliers. Maybe they scale up production. The FDA doesn’t assume everything stays the same. That’s where SUPAC-IR (Scale-Up and Post-Approval Changes for Immediate Release) comes in. Any change-no matter how small-requires new dissolution testing. The generic must still match the original profile. If it doesn’t, the FDA can require new bioequivalence studies or even pull the product. This isn’t theoretical. In 2023, the FDA rejected several ANDAs because the dissolution profiles shifted after a minor change in excipients. The company had to redo the entire method development process.The FDA’s Dissolution Database: A Secret Weapon

Manufacturers don’t start from scratch. The FDA maintains a public database with recommended dissolution methods for over 2,800 drug products. It’s updated regularly and includes exact conditions: apparatus type, rotation speed, buffer composition, sampling times. This database saves companies months of trial and error. If your drug is in the database, you follow the method. If it’s not, you have to develop and justify your own. But even then, the FDA expects you to use the same principles: simulate the body, test under multiple conditions, prove your method is robust.

Why This System Works

Before dissolution testing became standard, generic manufacturers had to run full bioequivalence studies in people. That cost millions and took years. Now, for many drugs, it’s done in a lab in weeks. Dr. Lawrence Yu, former FDA official, said it best: dissolution testing reduces the regulatory burden without sacrificing quality. It’s a smart balance-protecting patients while making generics affordable and fast to market. For BCS Class I drugs, the FDA even grants biowaivers. That means no human studies at all. Just a dissolution profile that matches the brand. This is why so many common generics-like metformin or atorvastatin-are approved so quickly.What’s Next?

The FDA is exploring ways to make dissolution testing even smarter. One idea is using physiologically based dissolution methods-liquids that more closely mimic the actual environment of the gut, including enzymes and bile salts. There’s also talk of extending biowaivers to BCS Class III drugs (high solubility, low permeability). If proven safe, this could cut development time for even more generics. But the FDA’s core message hasn’t changed: dissolution testing must be product-specific. You can’t copy-paste a method from one drug to another. Each drug has its own behavior. The test must reflect that.Bottom Line

You don’t need to know the details of dissolution testing to take your generic medication. But you should know this: the FDA doesn’t approve generics based on price or speed. They approve them because the pill dissolves the same way as the brand. And that’s what keeps you safe.Is dissolution testing required for all generic drugs?

No, not all. Dissolution testing is required for oral solid doses (tablets, capsules), oral semi-solids, and suspensions. It’s not needed for liquids, injections, or topical creams because those are already in solution or don’t rely on dissolution for absorption.

What’s the difference between dissolution testing and bioequivalence studies?

Dissolution testing is done in a lab using machines and liquids-it’s in vitro. Bioequivalence studies involve giving the drug to people and measuring blood levels-it’s in vivo. Dissolution testing is a predictive tool. If two drugs dissolve the same way, they’re likely to behave the same in the body. For many drugs, this replaces the need for human studies.

Can a generic drug pass dissolution testing but still be unsafe?

It’s rare, but possible. Dissolution testing catches most issues, especially with immediate-release drugs. But for complex formulations-like those with coatings or polymers-there can be hidden differences in how the drug releases over time. That’s why the FDA requires methods that are discriminatory: they must be able to spot differences that could affect safety or effectiveness.

Why does the FDA use f2 similarity factor?

The f2 factor compares the entire dissolution curve-not just one point. It looks at how both drugs release over time. A score of 50 or higher means the curves are statistically similar. A lower score suggests the drug may behave differently in the body, even if it meets the 80% in 45 minutes rule.

How long does it take to develop a dissolution method?

For simple immediate-release drugs, it can take 2-4 months. For complex modified-release products, especially those with low solubility, it can take 6-12 months. Manufacturers must test under multiple conditions, validate the method, and prove it’s reproducible across labs and equipment.

Are FDA dissolution standards the same worldwide?

No. While many countries follow similar principles, the FDA’s standards are among the strictest. The European Medicines Agency (EMA) and Health Canada have comparable frameworks, but exact acceptance criteria, pH conditions, and f2 thresholds can vary. A drug approved in the U.S. might need additional testing to meet other countries’ requirements.

Harriet Wollaston

This is actually kind of beautiful how science keeps us safe without us even noticing. I used to worry about generics, but now I get it-they’re not cheaper because they’re worse, they’re cheaper because we stopped testing on humans for every single pill.

Emma Sbarge

So let me get this straight-we’re trusting a machine in a lab to tell us if a pill will save my life, but we won’t let people get cheap insulin because ‘it’s not FDA-approved’? This system works until it doesn’t, and then people die.

Rawlson King

There’s a reason the FDA’s standards are the gold standard. Other countries cut corners. Their generics cause liver damage, heart arrhythmias, you name it. If you want to risk your health, go buy Indian or Chinese generics. But don’t pretend the FDA is the problem.

Shelby Ume

For years, I thought generics were just knockoffs. Then I learned about dissolution testing. It’s not magic-it’s meticulous, repeatable science. The FDA doesn’t wing it. They have protocols for protocols. And yes, it’s boring as hell, but that’s what keeps you from overdosing on a fake version of your blood pressure med.

People complain about drug prices, but the real hero here is the guy in the lab running 500 dissolution runs to prove his tablet releases 80% in 45 minutes. No one cheers for him. But he’s the reason your $4 metformin works.

And the f2 factor? That’s not just a number. It’s a curve. It’s the difference between ‘close enough’ and ‘actually equivalent.’ The FDA doesn’t accept ‘close.’ They demand alignment. That’s why we don’t have another Vioxx.

Himmat Singh

It is a fallacy to assume that dissolution testing is sufficient for bioequivalence. The human gastrointestinal tract is not a beaker. Variability in gastric emptying, pH, microbiota, and food interactions renders in vitro data inherently incomplete. To equate the two is to ignore decades of pharmacokinetic research.

Bruno Janssen

I’ve been on generic lisinopril for 8 years. I swear it doesn’t work like the brand. My BP spikes. I get dizzy. I’ve tried three different generics. Only the brand works. But the FDA says they’re all the same. So who’s lying?

Richard Ayres

It’s fascinating how much thought goes into something most people never think about. The alcohol challenge test for extended-release meds? That’s brilliant. I never realized drinking a beer with my OxyContin generic could literally kill me. Thanks for making that visible.

Sheldon Bird

Exactly! And that’s why we need more transparency. If the FDA published dissolution profiles publicly, people could compare their own meds. I’d feel way better knowing my generic matches the brand’s curve-not just some number.

Also, big props to the scientists who do this work. No applause, no headlines, just quiet, precise science keeping millions safe.

Donna Hammond

For low-solubility drugs, the f2 factor is everything. I work in pharma QA, and I’ve seen companies fail ANDAs because their curve dipped at 15 minutes-even though they hit 80% at 45. That’s the difference between ‘approved’ and ‘rejected.’ It’s not about the total, it’s about the pattern.

And yes, the FDA’s database is a lifesaver. One lab spent 9 months developing a method… then found it was already in the database. Saved them $200K.

Tommy Watson

bro the fda is just a glorified lab tech with a clipboard. they dont care if your generic makes you vomit for 3 days as long as it 'dissolves at 80%'. i took a generic adderall and felt like i was being crushed by a truck. brand? smooth as butter. same pill? nope.

Karen Mccullouch

Let’s be real-this whole system only works because the FDA is run by Americans. If this was a European or Indian agency, they’d approve anything with a barcode. We’re not just regulating drugs-we’re protecting American ingenuity from cheap foreign knockoffs.

Scott Butler

And yet, we let China make 80% of our active ingredients. Meanwhile, the FDA spends millions testing dissolution curves while our supply chain’s held hostage by a foreign dictatorship. This is a luxury we can’t afford anymore.