Ever wonder why a night out can leave you feeling swollen the next morning? The link between edema and alcohol is more than a coincidence - it’s a mix of how booze messes with your body’s fluid balance, liver health, and heart function. Below we break down what’s really happening, who’s at risk, and how you can keep swelling at bay without giving up the occasional drink.

Quick Takeaways

- Alcohol can trigger fluid retention by affecting liver, kidneys, and heart.

- Chronic drinking raises the risk of liver cirrhosh, hypertension, and cardiomyopathy - all common causes of edema.

- Even moderate intake may worsen edema if you already have kidney disease or low albumin levels.

- Reducing alcohol, staying hydrated, and managing salt intake are first‑line steps.

- Seek medical help if swelling appears suddenly, is painful, or is accompanied by shortness of breath.

Before diving into the science, let’s pin down the basics.

What Is Edema?

Edema is a medical term for abnormal fluid accumulation in the body’s tissues, most often showing up as swelling in the feet, ankles, legs, or hands. The fluid is primarily water mixed with electrolytes like sodium and potassium. When the balance between fluid pressure inside blood vessels and the surrounding tissue is disrupted, fluid leaks out and pools.

Edema isn’t a disease itself; it’s a symptom of underlying issues such as heart failure, liver disease, kidney dysfunction, or medication side‑effects. Recognizing the cause is crucial because treatment targets the root problem, not just the swelling.

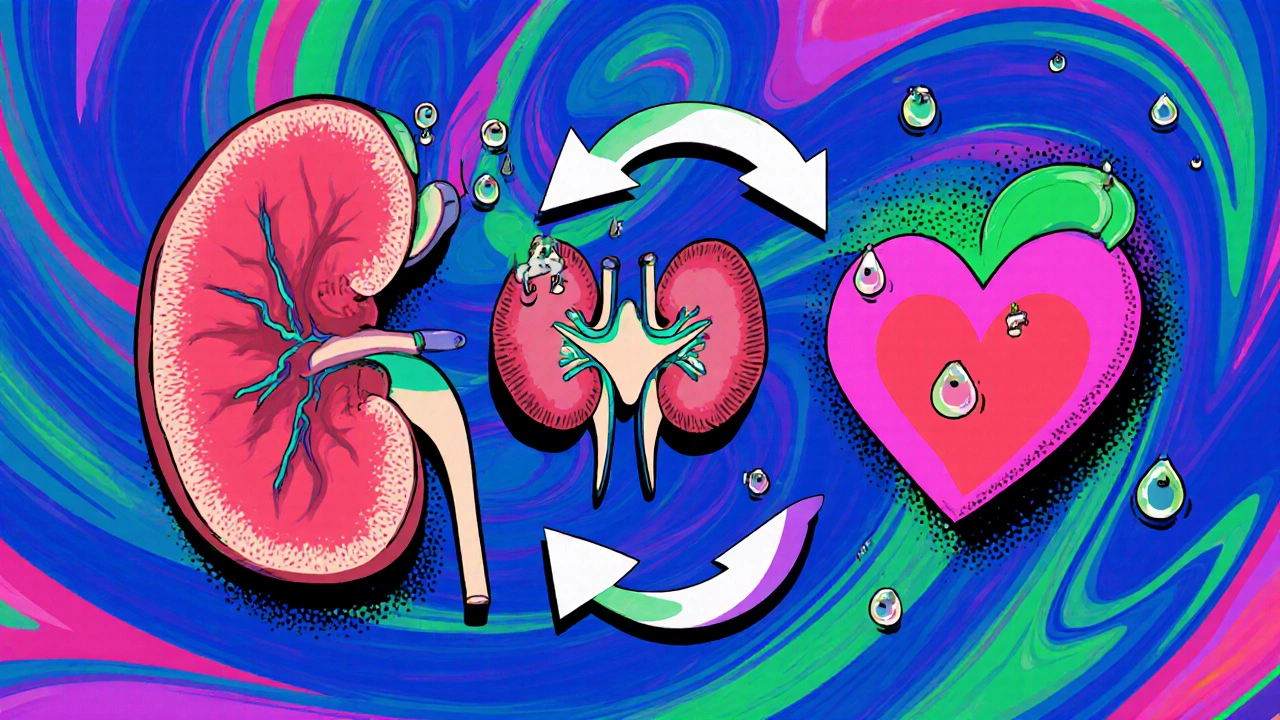

How Alcohol Affects Fluid Balance

Alcohol is a diuretic - it makes you pee more - but the story doesn’t end there. While the initial rush can lead to temporary dehydration, the body soon compensates by retaining water. Here’s the chain reaction:

- Increased Urination: Alcohol suppresses the release of antidiuretic hormone (ADH), causing the kidneys to excrete more water.

- Rebound Retention: As blood volume drops, your body releases hormones (renin‑angiotensin‑aldosterone system) that signal the kidneys to hold onto sodium and water.

- Electrolyte Imbalance: Excessive urination strips the body of electrolytes, prompting cells to retain water to maintain osmotic balance.

- Alcohol Metabolism: The liver metabolizes ethanol into acetaldehyde, a toxic compound that generates inflammatory stress, further disturbing fluid regulation.

The net effect? Even a single evening of heavy drinking can leave you waking up with puffier feet or a bloated face.

Key Mechanisms Linking Alcohol to Edema

Below is a concise look at the major pathways where alcohol directly or indirectly fuels fluid retention.

| Organ/System | Alcohol‑Induced Change | Resulting Edema Risk |

|---|---|---|

| Liver | Fatty infiltration → Fibrosis → Cirrhosis | Reduced albumin production lowers oncotic pressure, causing fluid to leak into the abdomen (ascites) and legs. |

| Kidneys | Alcohol‑induced hypertension & tubular injury | Impaired sodium excretion leads to systemic fluid overload. |

| Heart | Alcoholic cardiomyopathy & weakened ventricular contraction | Decreased cardiac output raises venous pressure, pooling blood in lower limbs. |

| Vascular System | Vasodilation followed by compensatory vasoconstriction | Altered capillary permeability permits fluid leakage. |

| Nervous System | Disrupted autonomic regulation of ADH | Fluctuating urine output creates rebound retention. |

Who’s Most Vulnerable?

Not everyone who enjoys a pint will develop edema, but certain groups face higher odds:

- Chronic heavy drinkers: Regular consumption >14 drinks/week for men and >7 for women accelerates liver and heart damage.

- People with pre‑existing liver or kidney disease: Their organs already struggle to manage fluid, so alcohol pushes them over the edge.

- Individuals on certain medications: Diuretics, ACE inhibitors, or NSAIDs can interact with alcohol, worsening fluid retention.

- Elderly adults: Age‑related decline in renal function makes them sensitive to any diuretic effect.

- Those with poor nutrition: Low protein intake reduces albumin, compounding the liver’s inability to hold fluid in vessels.

Signs and Symptoms to Watch

Edema shows up in different ways depending on the underlying cause. Keep an eye out for:

- Puffy ankles or feet that don’t improve after elevating the legs.

- Swelling around the eyes in the morning.

- Rapid weight gain (2-3 kg in a few days) without a change in diet.

- Stiff, shiny skin that retains a dimple when pressed (pitting edema).

- Shortness of breath or chest tightness - possible sign of pulmonary edema.

- Abdominal fullness or a “gaseous” feeling - could indicate ascites.

If any of these appear after a night of drinking, it’s a red flag that your body is struggling to regulate fluid.

Prevention and Management Strategies

Good news: most of the steps to curb alcohol‑related edema are lifestyle‑based and don’t require expensive treatments.

1. Moderate or Cut Back on Alcohol

Guidelines from the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) suggest no more than 10 standard drinks per week for men and 4 for women, with at least two drink‑free days. If you already have liver or heart issues, aim for complete abstinence.

2. Stay Hydrated With Water

After drinking, sip water throughout the evening and the next morning. Proper hydration reduces the rebound retention triggered by ADH suppression.

3. Watch Your Sodium Intake

High‑salt foods (processed snacks, fast food, canned soups) amplify fluid retention. Aim for under 2,300 mg of sodium a day, or lower if you have hypertension.

4. Boost Protein and Vitamin C

Protein supports albumin production. Include lean meats, beans, dairy, or plant‑based proteins. Vitamin C helps protect liver cells from oxidative damage caused by acetaldehyde.

5. Use Diuretics Only Under Medical Supervision

Prescription diuretics (e.g., furosemide) can relieve severe swelling, but they interact with alcohol and may cause electrolyte loss. Never self‑medicate.

6. Regular Physical Activity

Walking, swimming, or low‑impact aerobics promotes venous return, especially important for those prone to lower‑leg edema.

7. Check Your Medications

Some drugs, like NSAIDs or certain blood pressure meds, increase fluid retention when mixed with alcohol. Talk to your GP about safer alternatives.

When to Seek Professional Help

Swelling can be harmless, but it can also signal serious conditions. Schedule a doctor’s appointment if you notice:

- Sudden, severe swelling in one leg (possible deep‑vein thrombosis).

- Shortness of breath, coughing up pink frothy sputum (pulmonary edema).

- Abdominal distension with a feeling of heaviness (ascites).

- Painful or warm skin over a swollen area.

- Persistent swelling that lasts more than a week despite lifestyle tweaks.

Medical evaluation may involve blood tests (liver enzymes, albumin, kidney function), ultrasound of the abdomen, and echocardiography to assess heart health.

Bottom Line

Alcohol isn’t just a temporary disruptor of your sleep - it can set off a cascade that leads to fluid retention, especially if your liver, kidneys, or heart are already under stress. By moderating intake, staying well‑hydrated, and keeping an eye on diet and medication interactions, you can dramatically cut down the risk of edema. And if swelling shows up unexpectedly, don’t shrug it off; early medical assessment can prevent complications down the line.

Can occasional binge drinking cause lasting edema?

A single binge may cause temporary puffiness due to fluid shifts, but lasting edema usually requires repeated heavy drinking that damages liver or heart function.

Is it safe to use over‑the‑counter diuretics while drinking?

No. OTC diuretics combined with alcohol can trigger severe dehydration and electrolyte imbalances. Always consult a doctor before mixing.

How quickly does swelling improve after stopping alcohol?

If swelling is due solely to alcohol‑induced fluid shifts, you may notice improvement within 2‑3 days of abstinence. Structural issues like cirrhosis take longer and need medical treatment.

Does low‑salt diet help even if I don’t drink?

Yes. Reducing sodium eases the burden on kidneys and heart, lowering overall fluid retention risk, regardless of alcohol intake.

Can herbal supplements reverse alcohol‑related edema?

Some herbs, like dandelion root, have mild diuretic effects, but they won’t fix organ damage from chronic drinking. Use them only as a complement to medical advice.

Felix Chan

Totally get how nasty that morning puffiness feels, but the good news is you can dial it back with a few simple habits. Swap that last shot for a glass of water, keep a water bottle handy, and aim for at least eight glasses a day. Cut down on salty snacks, throw in a quick walk, and you’ll see the swelling melt away faster than a cheap beer foam. Small tweaks add up, and you’ll still enjoy the occasional drink without the bloat.

Christopher Burczyk

While the anecdotal advice is well‑intentioned, the pathophysiology merits a more rigorous exposition. Alcohol suppresses antidiuretic hormone, precipitating a cascade of renin‑angiotensin activation that culminates in sodium and water retention. Consequently, individuals with compromised hepatic synthetic function experience a pronounced decrease in oncotic pressure, fostering ascites and peripheral edema. Moreover, chronic ethanol exposure precipitates cardiomyopathic remodeling, which further elevates venous hydrostatic pressure. In sum, mitigation strategies must address both hormonal rebalance and organ‑specific damage.

Caroline Keller

Oh my god the swelling after a night out is like a horror movie scene. You think you’re fine and then your ankles look like balloons. It’s not just a coincidence it’s your body screaming for help. You keep drinking and ignore the warning signs and then wonder why you look like a marshmallow. The guilt is real and the drama never ends.

dennis turcios

The post correctly outlines the physiological loop, but it glosses over the quantitative aspect of sodium balance. In most cases, a 2‑gram excess of dietary sodium translates to roughly a 0.5‑liter increase in extracellular fluid, which is clinically observable. Ignoring this numeric relationship can lead readers to underestimate the impact of their snack choices. A more data‑driven discussion would strengthen the argument.

Penny Reeves

One must appreciate the nuanced interplay between hepatic albumin synthesis and oncotic gradients; it is not merely a matter of “drink less”. The editorial fails to acknowledge the hierarchical nature of compensatory mechanisms, wherein renal adaptation precedes hepatic decompensation. An erudite reader would demand a stratified risk matrix rather than a blanket recommendation.

Sunil Yathakula

Hey! I totally feel you. When you’re stuck with that puffy feeling, just try to drink water in sips after the party – it helps your body rebalance. Also, try to keep a little snack like banana or nuts; they give you potassium which counteracts the sodium. And don’t forget to stretch your legs a bit before bed, it can move the fluid out. You’re not alone in this, keep it up!

Catherine Viola

It is incumbent upon the medically informed citizen to recognize that the purported “harmlessness” of occasional intoxication is a façade engineered by pharmaceutical conglomerates. The prevailing narrative conceals a coordinated effort to normalize renal stress, thereby ensuring a perpetual market for diuretic agents. One must therefore question: who benefits from the chronic under‑reporting of ethanol‑induced endothelial dysfunction? The answer lies in the intersection of profit‑driven research and regulatory capture.

sravya rudraraju

Thank you for bringing attention to this topic; it is often overlooked in everyday health conversations. While the biochemical pathways are complex, the practical steps remain accessible to anyone willing to make modest adjustments. Prioritizing hydration, moderating sodium intake, and incorporating low‑impact aerobic activity can collectively improve venous return and mitigate peripheral fluid accumulation. Additionally, regular monitoring of liver function tests provides an objective metric for assessing progress. I encourage readers to view these recommendations not as restrictions but as empowering choices that enhance overall wellbeing.

Ben Bathgate

Yo just ditch the booze and you’re good.

Ankitpgujjar Poswal

Listen, you’ve got the power to take control – smash that habit, hit the gym hard, and flood your body with water. No more excuses; the swelling won’t disappear on its own. Push yourself, stay relentless, and you’ll see the difference in days.

Nicole Boyle

From a pathophysiological standpoint, the interplay of ADH suppression and RAAS activation constitutes a classic negative feedback loop that culminates in extracellular fluid sequestration. Practitioners often refer to this as a “fluid‑shunt” phenomenon, observable via bioimpedance spectroscopy. Integrating these metrics into patient education can demystify the mechanistic basis of edema for lay audiences.

Thokchom Imosana

Let us begin by acknowledging that the mainstream medical discourse on alcohol‑induced edema is, in many respects, a carefully curated veneer designed to obscure deeper geopolitical machinations. The first point of contention lies in the omission of petrochemical by‑products that infiltrate our water supply, subtly amplifying the diuretic impact of ethanol while simultaneously destabilizing renal osmoregulation. Moreover, the covert sponsorship of research institutions by industries vested in the sale of antihypertensive pharmaceuticals creates a feedback loop wherein mild edema is normalized, thereby perpetuating dependence on prescription diuretics.

Second, the selective emphasis on “moderate drinking guidelines” ignores the sociocultural engineering aimed at embedding alcohol consumption into the fabric of daily life, a strategy that serves both tax revenue optimization and the perpetuation of a consumerist ethos.

Third, peer‑reviewed journals have, on multiple occasions, published articles under pseudonyms that align with corporate agendas, effectively muting dissenting voices that would otherwise highlight the cumulative toxicity of acetaldehyde metabolites on hepatic sinusoidal endothelium. This aligns with the broader narrative of information asymmetry deliberately cultivated by shadowy consortiums that profit from chronic disease management.

Fourth, the physiological explanations offered in popular health articles frequently neglect to mention the role of melatonin suppression, a consequence of nocturnal alcohol intake that exacerbates capillary permeability through dysregulated circadian signaling.

Fifth, there exists an underappreciated link between the micro‑plastics embedded in alcoholic beverages and the induction of low‑grade inflammatory states, which synergize with the oxidative stress from acetaldehyde to precipitate endothelial dysfunction.

Sixth, the prevalence of “social drinking” narratives distracts the populace from recognizing that the majority of edema cases in developed nations are statistically correlated with high‑intensity alcohol marketing campaigns funded by multinational conglomerates.

In conclusion, while the surface‑level advice to hydrate, limit sodium, and moderate intake holds pragmatic merit, it functions as an appeasement strategy designed to maintain the status quo. A truly informed populace must interrogate the structural underpinnings of these health recommendations, demand transparency in research funding, and advocate for policies that decouple alcohol promotion from public health messaging.