Sinus-Breathing Connection Risk Checker

How Sinus Infections Affect Your Breathing

This tool helps you assess your risk of sinus-related breathing issues based on the symptoms discussed in the article. It's not a substitute for professional medical advice, but can help you decide when to seek care.

Symptom Assessment

Ever wondered why a simple cold sometimes makes it feel impossible to catch a breath? The link between sinus infections and breathing disorders is more than a coincidence - it’s a two‑way street where inflammation in one part of the airway fuels trouble in another. Below you’ll find a straight‑forward guide that walks you through what’s happening, which conditions get hit the hardest, and how to break the cycle.

- Learn how sinus infections aggravate common breathing disorders.

- Identify warning signs that a sinus issue is worsening your lungs.

- Get practical, doctor‑approved treatment steps that target both problems.

- Pick up prevention tips to keep your airways clear year‑round.

What Exactly Are Breathing Disorders?

Breathing disorders is a group of medical conditions that impair normal airflow in the lungs and airways. They range from the well‑known (asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease - COPD) to the less obvious (sleep‑related breathing problems, restrictive lung disease). The common thread? All of them cause the body to work harder to get enough oxygen, which can lead to fatigue, reduced activity, and a cascade of other health issues.

What Is a Sinus Infection?

Sinus infection is a medical condition where the lining of the sinus cavities becomes inflamed and filled with mucus, often due to bacteria, viruses, or fungi. When the sinuses swell, they block normal drainage, creating a perfect breeding ground for microbes. Symptoms include facial pressure, nasal congestion, thick discharge, and sometimes fever.

Why the Two Often Collide

Both the lungs and the sinuses belong to the same continuous airway. When the sinuses are clogged, the body’s natural cleaning system - called mucociliary clearance is a process where tiny hair‑like cilia move mucus and trapped particles out of the airways - slows down. Stagnant mucus can harbor bacteria and inflammatory cells, which then spill over into the lower airway.

Inflammatory messengers, known as inflammatory cytokines are proteins released by immune cells that signal and amplify inflammation throughout the body, travel from the sinus lining into the bloodstream and reach the lungs. The result? Airways become hyper‑responsive, making them more likely to spasm (as in asthma) or produce excess mucus (as in COPD).

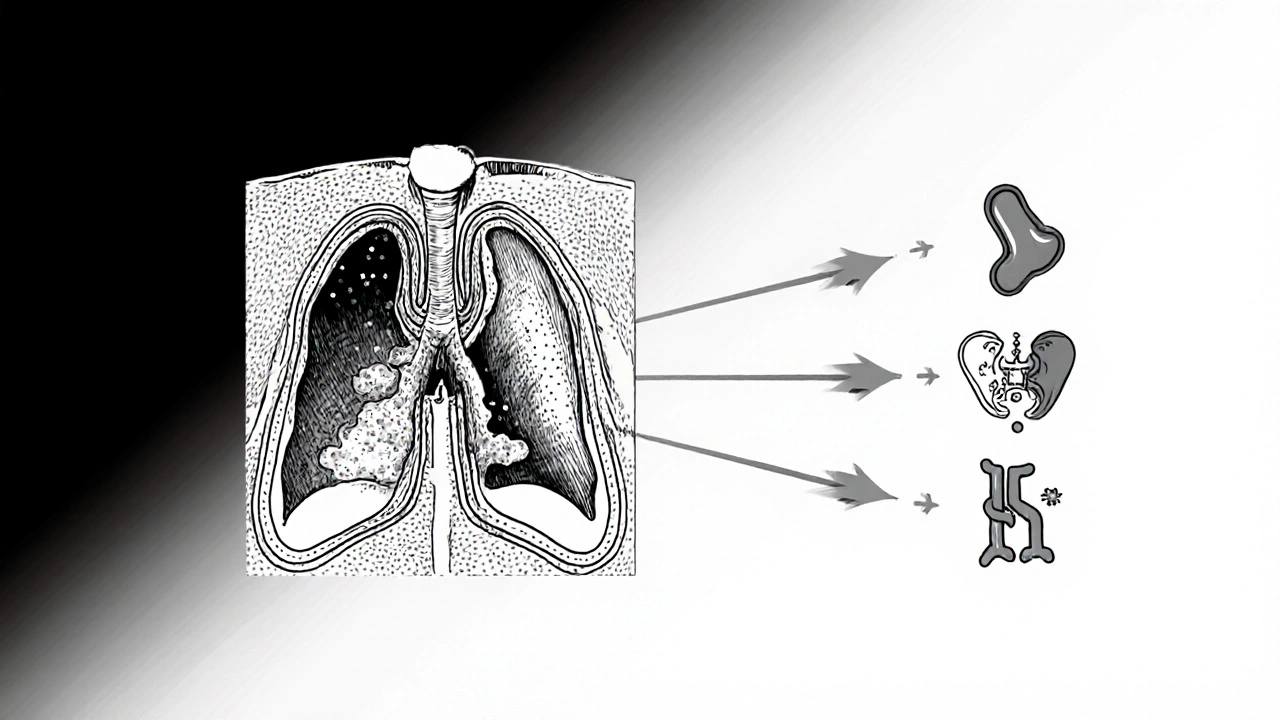

Breathing Disorders Most Affected by Sinus Infections

Below are the three conditions that feel the biggest push from sinus problems. Each definition includes a microdata tag for easier knowledge‑graph integration.

Asthma is a chronic inflammatory disease of the airways that causes episodes of wheezing, shortness of breath, chest tightness, and coughing. For asthmatics, a clogged sinus can trigger an “asthma flare” because the inflamed mucus adds extra pressure on already sensitive bronchial tubes.

COPD is a progressive lung disease, usually caused by long‑term exposure to irritants like cigarette smoke, that leads to reduced airflow, chronic cough, and frequent infections. Sinus infections raise the bacterial load that COPD patients already struggle to clear, worsening breathlessness and increasing the risk of exacerbations.

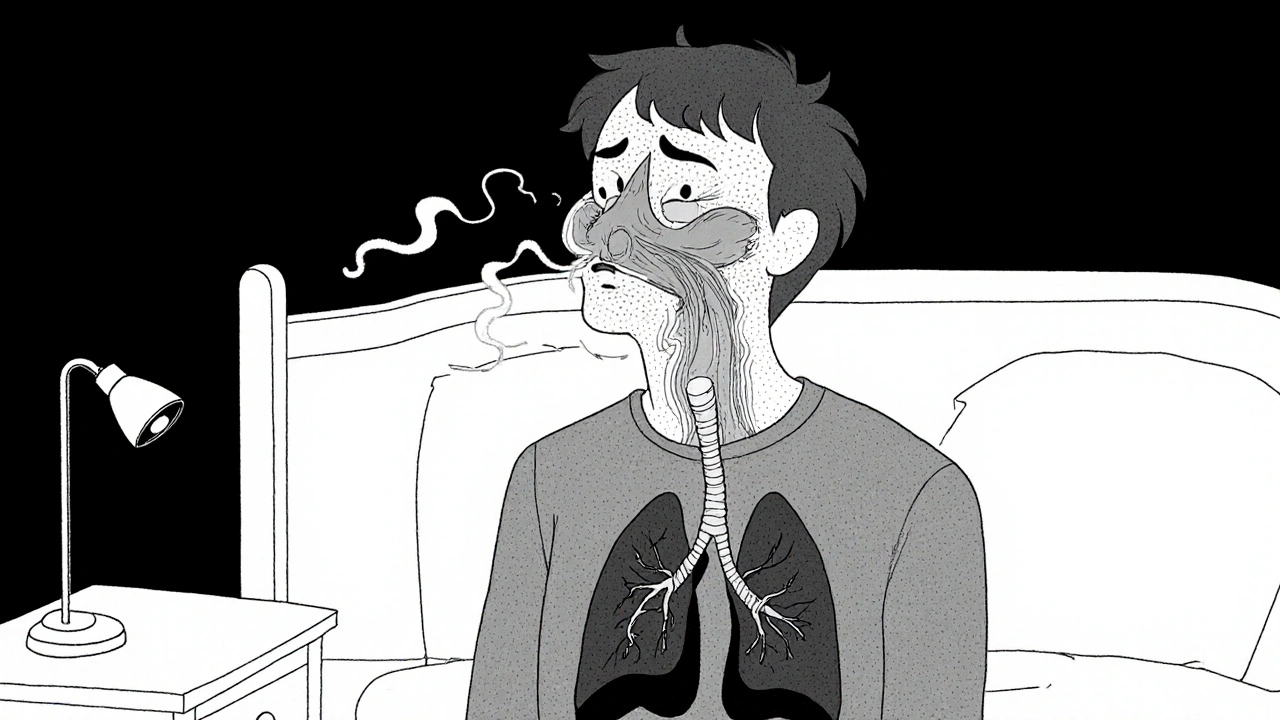

Sleep apnea is a disorder where the airway collapses temporarily during sleep, causing repeated pauses in breathing and fragmented sleep. Nasal congestion from sinusitis forces the person to breathe through the mouth, which can further destabilize the airway and intensify apnea episodes.

Spotting the Warning Signs

If you notice any of these signals, it’s a good hint that a sinus infection is getting in the way of your breathing health:

- Sudden increase in wheezing or coughing after a cold.

- Chest tightness that feels worse when you’re congested.

- Frequent nighttime awakenings with a feeling of “blocked air.”

- Reduced response to usual inhaler or bronchodilator doses.

- New or worsening facial pain that coincides with shortness of breath.

When these pop up, a quick check‑up can differentiate between a simple upper‑respiratory flare and a full‑blown lower‑airway escalation.

Treatment Strategies That Hit Both Targets

Because the sinuses and lungs talk to each other, addressing one side often calms the other. Here are the most effective steps:

- Saline nasal irrigation: Flushing out mucus reduces bacterial load and restores mucociliary clearance. Do it twice a day with a neti pot or squeeze bottle.

- Short‑course antibiotics (if bacterial): A physician may prescribe amoxicillin‑clavulanate for 7‑10days when cultures suggest bacterial growth. This helps resolve the sinus infection faster, cutting the inflammatory cascade.

- Intranasal corticosteroids: Sprays like fluticasone reduce sinus wall swelling and the release of inflammatory cytokines, easing both nasal and bronchial irritation.

- Leukotriene modifiers (e.g., montelukast): These pills block a specific inflammatory pathway that’s common to asthma and sinus inflammation, providing dual relief.

- Allergy management: If allergic rhinitis is the underlying trigger, antihistamines or allergy shots can prevent sinus blockage before it starts.

- Proper inhaler technique: Even the best asthma medication won’t work if the airway is clogged. Ensure you’re using a spacer and breathing slowly to get the medication deep into the lungs.

- Humidified air: Using a cool‑mist humidifier at night keeps nasal passages moist, preventing the thick mucus that can travel down to the lungs.

Remember, any medication plan should be reviewed by a health professional, especially if you have multiple chronic conditions.

Quick Comparison: How Sinus Infections Affect Asthma vs. COPD

| Aspect | Asthma | COPD |

|---|---|---|

| Typical trigger | Allergic or viral sinus inflammation | Chronic bacterial sinusitis |

| Increase in symptoms | Wheezing, tighter chest, need for rescue inhaler | Worsened dyspnea, increased sputum, higher exacerbation risk |

| Response to nasal steroids | Often improves asthma control | May reduce COPD flare frequency |

| Long‑term outlook | Better disease stability when sinus health is maintained | Slower progression if sinus infections are promptly treated |

Prevention: Keeping Your Airways Clear All Year

Prevention is easier than treating a flare‑up. Adopt these habits:

- Stay hydrated - water thins mucus and supports ciliary motion.

- Wash hands frequently to block germs that start sinus infections.

- Use a humidifier in dry seasons; clean it weekly to avoid mold.

- Consider a low‑dose intranasal steroid if you have seasonal allergies.

- Avoid smoking and second‑hand smoke - they impair mucociliary clearance.

- Get your flu and COVID‑19 vaccines - viral illnesses often precede sinusitis.

By keeping the upper airway healthy, you give your lungs a better chance to breathe easily.

Key Takeaways

- Sinus infections can worsen asthma, COPD, and sleep apnea through shared inflammation pathways.

- Watch for sudden changes in breathing when you have a cold or sinus congestion.

- Treat both sides: saline rinses, nasal steroids, and appropriate antibiotics can break the feedback loop.

- Long‑term prevention - hydration, humidified air, and allergy control - helps keep both sinuses and lungs happy.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can a sinus infection cause an asthma attack?

Yes. When sinuses swell, they release inflammatory cytokines that make the airways extra sensitive. This can trigger wheezing, chest tightness, and the need for rescue medication.

Do I need antibiotics for every sinus infection?

Not always. Most sinus infections start viral and clear up with rest and saline rinses. Doctors prescribe antibiotics only when a bacterial cause is confirmed or symptoms last longer than 10days.

Will using a nasal steroid help my COPD?

Nasal steroids reduce sinus inflammation, which can lower the frequency of COPD exacerbations caused by mucus spill‑over. They are not a replacement for COPD inhalers but work well as a supportive therapy.

How does allergic rhinitis fit into this picture?

Allergic rhinitis inflames the nasal lining, making sinus blockage more likely. Managing allergies with antihistamines or immunotherapy can therefore protect both the sinuses and the lower airway.

Is it safe to use a neti pot every day?

Yes, as long as you use distilled, sterile, or boiled‑then‑cooled water. Daily irrigation helps keep mucus thin and reduces bacterial growth in the sinuses.

Louie Lewis

One must consider that the sinus‑lung axis is not merely a physiological curiosity but a deliberately obscured conduit through which the medical establishment perpetuates a cycle of dependency and profit

Eric Larson

Wow!!! This article blows the lid off the whole sinus‑breathing connection!!! I mean, who knew that a simple nasal drip could unleash a tornado of wheeze in the lungs??? The drama is real, folks, and the stakes are sky‑high!!!

Kerri Burden

The pathophysiology described aligns with the concept of united airway disease, wherein mucociliary dysfunction and cytokine spillover create a feedback loop that exacerbates both asthma and COPD. Clinically, monitoring fractional exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO) may provide insight into upper airway inflammation that could predict lower airway instability.

Joanne Clark

Honestly the article is definetly spot on but it coulda used more real life examples like when my aunt's sinusitis sent her asthma into a full on panic attack she couldnt breathe a single second.

Tushar Agarwal

Great overview! 😊 The neti‑pot tip especially helped me during allergy season. Keeping the water sterile is key – I always boil it and let it cool before rinsing. Stay healthy!

Richard Leonhardt

In essence, integrating intranasal corticosteroids with standard bronchodilator therapy constitutes a synergistic approach that addresses both upper and lower airway inflammation. Patients should be counseled on proper inhaler technique to maximize drug deposition, and periodic assessment of sinus symptomatology is advisable for optimal disease control.

Shaun Brown

When evaluating the interplay between sinusitis and chronic respiratory conditions, it is prudent to adopt a holistic framework that encompasses environmental, immunologic, and behavioral factors. First, consider the role of allergen exposure; seasonal pollen can simultaneously inflame the nasal mucosa and exacerbate bronchial hyper‑responsiveness, creating a perfect storm for asthma attacks. Second, the presence of bacterial superinfection in the sinuses can act as a reservoir for pathogens that colonize the lower airway, thereby increasing the frequency of COPD exacerbations. Third, the mechanical obstruction caused by swollen turbinates forces oral breathing, which bypasses the innate filtration mechanisms of the nasal passages and leads to dry, irritated bronchi. Fourth, systemic inflammatory mediators such as interleukin‑5 and tumor necrosis factor‑alpha travel via the bloodstream, amplifying inflammation in distant lung tissue. Fifth, patients with obstructive sleep apnea often experience nocturnal hypoxia, which in turn promotes inflammatory cytokine release, further destabilizing asthma control. Sixth, the use of saline irrigation not only clears mucus but also restores ciliary function, facilitating mucociliary clearance throughout the respiratory tract. Seventh, intranasal corticosteroids have been shown in randomized trials to reduce the rate of asthma exacerbations by dampening local cytokine production. Eighth, leukotriene receptor antagonists, such as montelukast, provide a dual benefit by blocking leukotriene pathways implicated in both sinusitis and lower airway constriction. Ninth, adherence to a consistent inhaler regimen remains paramount; even the most potent anti‑inflammatory agents are rendered ineffective if the patient fails to use the device correctly. Tenth, lifestyle modifications including smoking cessation, humidifier use, and adequate hydration synergize with pharmacologic therapy to maintain airway patency. Eleventh, vaccination against influenza and COVID‑19 mitigates viral triggers that commonly precipitate sinus infections and subsequent respiratory decompensation. Twelfth, regular follow‑up with an otolaryngologist can identify structural anomalies such as deviated septum that perpetuate chronic sinusitis. Thirteenth, pulmonary rehabilitation programs that incorporate breathing exercises may improve mucus clearance and reduce reliance on rescue medications. Fourteenth, patient education regarding early symptom recognition can prompt timely medical intervention before a minor sinus flare escalates into a severe respiratory event. Finally, a personalized management plan that integrates these evidence‑based strategies offers the best prospect for breaking the vicious cycle linking sinus disease and breathing disorders.

Damon Dewey

Sinus infections are just another excuse for pharma to sell more drugs.

Musa Bwanali

Listen up! If you keep ignoring nasal congestion you’ll sabotage your own lung health. Take control now, start daily saline rinses and never skip your inhaler technique drills. Your future self will thank you.

Allison Sprague

While the article is thorough, it unfortunately suffers from a few typographical oversights that detract from its credibility. For instance, “cicily” appears where “ciliary” was intended, and the table headings lack proper capitalization. Moreover, the recommendation to use “antibiotics for every sinus infection” contradicts current evidence‑based guidelines, which emphasize a watch‑ful waiting approach for viral etiologies. Nonetheless, the emphasis on integrated therapy is commendable, and the inclusion of evidence‑based adjuncts such as leukotriene modifiers adds substantial value. I encourage the author to proofread meticulously before publishing future pieces.

leo calzoni

People think they know it all but the real answer is simple – keep your nose clear or your lungs will suffer.

KaCee Weber

Hey everyone! 🌟 I just wanted to say how much I appreciate this deep dive into the sinus‑lung connection – it really opened my eyes to how interconnected our bodies truly are. 🌬️💧 The part about saline irrigation is pure gold; I’ve been using a neti pot for years and swear it keeps my breathing smooth during allergy season. 😌💦 Also, the reminder to stay hydrated is something we all forget, especially when we’re busy, but water really does thin mucus and helps cilia do their job. 🥤✨ For anyone battling asthma, remember that nasal steroids aren’t just for a stuffy nose – they can actually reduce the need for rescue inhalers, which is a game‑changer. 🙌💊 And let’s not overlook the power of proper inhaler technique; a spacer can make a huge difference in drug delivery. 🎯🗣️ Lastly, I love the preventive tips – wash your hands, avoid smoke, and get vaccinated. Small steps add up to big health wins! 🌈❤️ Keep sharing knowledge and supporting each other, folks! 🚀🤗

Sriram K

Thanks for the comprehensive guide. I would add that tracking symptom patterns in a diary can help differentiate whether a flare is sinus‑driven or a primary bronchial issue, enabling more targeted treatment. Also, consider referral to an ENT specialist if sinus infections become recurrent despite optimal medical therapy.