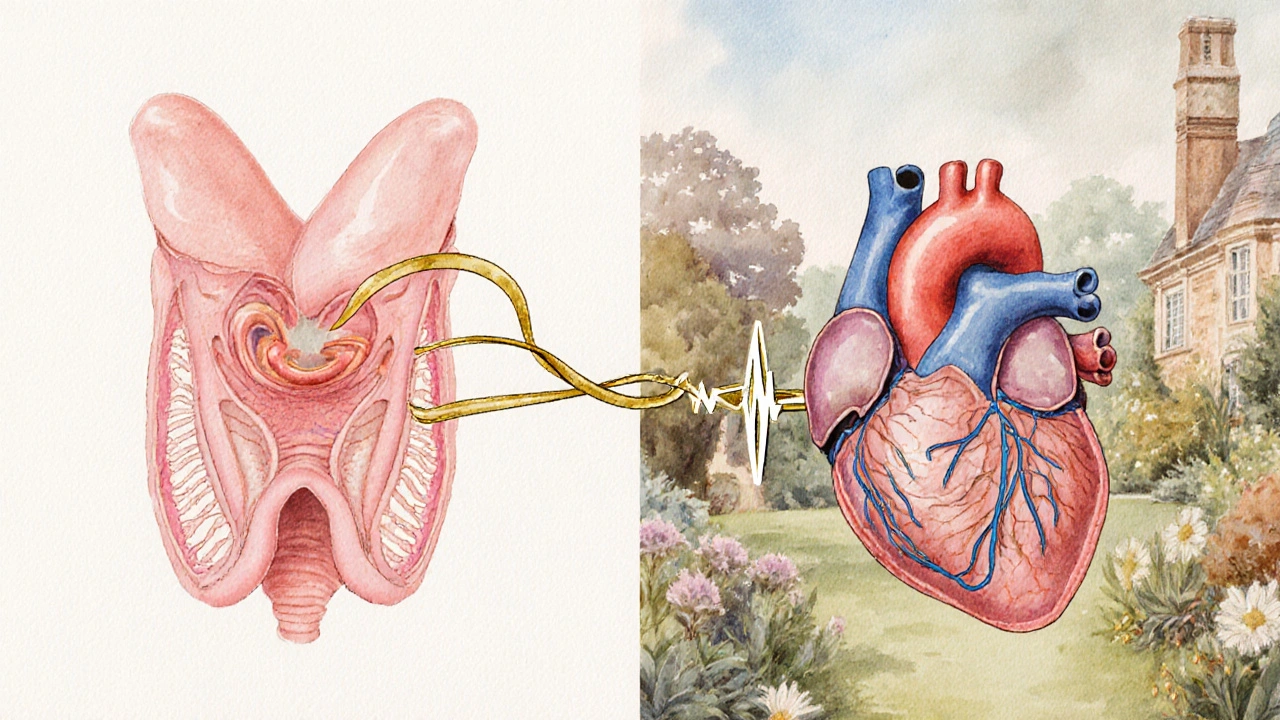

Thyroid disorder is a medical condition in which the thyroid gland produces too much or too little hormone, disrupting metabolism, energy levels, and, crucially, heart rhythm. When the thyroid goes haywire, the heart often follows suit, resulting in various cardiac arrhythmia abnormal heartbeats that are too fast, too slow, or irregular. Understanding this connection helps patients and clinicians catch warning signs early and manage both sides of the equation.

Key Takeaways

- Both hyper‑ and hypothyroidism can provoke specific arrhythmias.

- Atrial fibrillation is the most common thyroid‑related rhythm problem.

- Thyroid function tests (TSH, T3, T4) are essential in any unexplained arrhythmia work‑up.

- Treatment targets the thyroid imbalance first; beta‑blockers and anti‑arrhythmics are secondary tools.

- Lifestyle tweaks-diet, stress control, regular monitoring-reduce recurrence.

How Thyroid Hormones Talk to the Heart

Thyroid hormones (T3 and T4 the active and storage forms of thyroid hormone) bind to receptors in cardiac muscle cells. This binding boosts the expression of calcium‑handling proteins, speeds up the sino‑atrial node, and makes the heart more contractile. In simple terms, more hormone = a faster, more excitable heart; less hormone = a slower, less responsive heart.

The pituitary gland keeps the thyroid in check via TSH thyroid‑stimulating hormone that tells the thyroid how much hormone to make. When TSH is suppressed (as in hyperthyroidism) or elevated (as in hypothyroidism), the downstream effect on the heart can be dramatic.

Hyperthyroidism and Its Arrhythmias

In hyperthyroidism a state of excess thyroid hormone production, patients often notice a racing pulse, heat intolerance, and nervousness. These symptoms mirror what the heart experiences: increased heart rate, heightened contractility, and a propensity for irregular beats.

The hallmark rhythm disorder linked to hyperthyroidism is atrial fibrillation (AF) an irregular, often rapid heart rhythm originating from the atria. Studies from major cardiology societies show that up to 15% of newly diagnosed hyperthyroid patients develop AF, compared with <1% in the general population.

Other fast‑paced rhythms include sinus tachycardia a normal increase in heart rate above 100bpm and occasional premature atrial contractions. Rarely, high‑output states can trigger ventricular ectopy, especially if underlying heart disease co‑exists.

Hypothyroidism and Its Rhythm Effects

Conversely, hypothyroidism a deficiency of thyroid hormone production slows metabolism and quiets the heart. Patients may feel sluggish, cold, and may gain weight. The electrical consequences are a slower heart rate and, in some cases, abnormal pauses.

The most common rhythm issue here is bradycardia a heart rate below 60bpm, often symptomatic. Severe hypothyroidism can also cause low‑voltage QRS complexes diminished electrical signal amplitude on ECG, mimicking myocardial injury.

In rare cases, hypothyroidism predisposes to atrial flutter or even ventricular conduction delays, especially when accompanied by electrolyte disturbances.

Side‑by‑Side Comparison: Hyper‑ vs. Hypothyroidism

| Feature | Hyperthyroidism | Hypothyroidism |

|---|---|---|

| Typical TSH level | Suppressed (<0.1µIU/mL) | Elevated (>10µIU/mL) |

| Common arrhythmia | Atrial fibrillation, sinus tachycardia | Bradycardia, low‑voltage ECG |

| Resting heart rate | >100bpm | <70bpm |

| Management focus | Antithyroid drugs, radioiodine, beta‑blockers | Levothyroxine replacement, careful dose titration |

Diagnosing the Thyroid‑Heart Link

When a patient presents with an unexplained arrhythmia, a basic thyroid panel (TSH, free T4, sometimes free T3) should be ordered. An abnormal result changes the diagnostic pathway dramatically.

Electrocardiography (ECG) confirms the rhythm type, while Holter monitoring captures intermittent episodes. For hyperthyroid patients, a 24‑hour Holter often reveals episodes of rapid atrial fibrillation that resolve once the thyroid is euthyroid.

Imaging isn’t usually needed for the thyroid‑heart connection, but an echocardiogram can rule out structural heart disease that might exacerbate rhythm issues.

Managing Arrhythmias in Thyroid Disorders

The cornerstone is correcting the thyroid imbalance.

- Hyperthyroidism: Antithyroid medications (methimazole, propylthiouracil) or definitive therapies (radioactive iodine, surgery) normalize hormone levels. As T3/T4 drop, the heart’s excitability calms.

- Hypothyroidism: Levothyroxine replacement restores metabolic rate; dose is titrated to keep TSH within the target range (0.5-4.0µIU/mL).

While the thyroid is being stabilized, symptom‑focused cardiac drugs are often required.

- Beta‑blockers medications that blunt sympathetic stimulation of the heart (e.g., propranolol, atenolol) are first‑line for hyperthyroid‑induced tachyarrhythmias. They reduce heart rate, control tremor, and lower blood pressure.

- Anti‑arrhythmic drugs agents that modify cardiac electrophysiology to prevent abnormal beats such as amiodarone are used cautiously. Amiodarone itself contains iodine and can trigger thyroid dysfunction, so monitoring is essential.

- For persistent AF, electrical cardioversion or catheter ablation may be considered after thyroid function is normalized.

In hypothyroid‑related bradycardia, pacing is rarely needed; most patients respond to adequate levothyroxine dosing.

Lifestyle, Nutrition, and Prevention

Beyond medication, everyday habits influence both thyroid health and cardiac rhythm.

- Iodine intake: Both excess and deficiency can destabilize thyroid function. In Australia, iodised salt provides adequate levels for most people.

- Stress management: Chronic stress raises cortisol, which can interfere with thyroid hormone conversion and increase sympathetic tone, aggravating arrhythmias.

- Exercise: Moderate aerobic activity improves cardiovascular fitness and helps regulate heart rate variability, reducing the likelihood of AF episodes.

- Sleep hygiene: Poor sleep is linked to atrial fibrillation; aim for 7-9 hours per night.

Regular follow‑up labs (TSH every 6-12months) and yearly ECGs for high‑risk patients keep the two systems in sync.

Related Concepts and Conditions

Understanding the thyroid‑heart axis opens doors to other clinically relevant topics.

- Autoimmune thyroiditis an immune‑mediated inflammation of the thyroid, commonly Hashimoto’s disease can cause fluctuating hormone levels, leading to alternating tachy‑ and brady‑arrhythmias.

- Amiodarone‑induced thyrotoxicosis excess thyroid hormone caused by the iodine‑rich anti‑arrhythmic drug amiodarone is a paradoxical situation where treating the heart creates a thyroid problem.

- Pregnancy shifts thyroid physiology; gestational hyperthyroidism can precipitate supraventricular tachycardia, demanding careful monitoring.

- Thyroid nodules and cancer rarely affect rhythm directly, but surgeries near the neck can injure the recurrent laryngeal nerve, altering vagal tone and heart rate.

When to Seek Medical Help

If you notice any of these signals, call your doctor promptly:

- Rapid, irregular pulse (palpitations, shortness of breath)

- Unexplained dizziness, fainting, or chest discomfort

- Persistent fatigue combined with a feeling of “fluttering” in the chest

- New weight changes, heat/cold intolerance, or mood swings that coincide with heart symptoms

Early detection allows simultaneous treatment of the thyroid and the heart, dramatically improving outcomes.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can hyperthyroidism cause a heart attack?

Hyperthyroidism itself doesn’t directly cause a myocardial infarction, but the increased heart rate and higher cardiac output can strain coronary arteries, especially in people with pre‑existing plaque. Managing thyroid levels reduces this extra stress and lowers the indirect risk.

Why does levothyroxine sometimes cause palpitations?

If the dose is too high, free T4 rises and mimics a mild hyperthyroid state, leading to tachycardia and occasional atrial fibrillation. Regular TSH testing ensures the dose stays within the therapeutic window.

Is atrial fibrillation reversible after treating thyroid disease?

In up to 70% of cases, restoring a normal thyroid state restores sinus rhythm without the need for long‑term anti‑arrhythmic drugs. However, prolonged AF may cause atrial remodeling, making permanent rhythm control necessary.

Can low iodine intake trigger heart rhythm problems?

Severe iodine deficiency can lead to hypothyroidism, which may cause bradycardia and low‑voltage ECG patterns. In most developed regions, iodine deficiency is rare because of iodised salt programs.

Should I avoid caffeine if I have a thyroid‑related arrhythmia?

Caffeine can exacerbate tachyarrhythmias, especially when the thyroid is over‑active. Moderation (no more than 200mg per day) is a safe guideline, but individual tolerance varies.

Brian Rice

It is incumbent upon clinicians to routinely assess thyroid function when confronted with unexplained arrhythmias, as neglecting this interrelationship constitutes a dereliction of duty. The pathophysiological mechanisms linking hormone excess or deficiency to cardiac electrophysiology are well‑documented, and ethical practice demands their inclusion in diagnostic algorithms.

Stan Oud

So the article says thyroid issues cause heart rhythm changes-yeah, sure… But we’ve known this for decades? The hype seems unnecessary.

Jennifer Ramos

Great summary! I especially appreciate the clear link between TSH levels and atrial fibrillation-makes it easier for patients to understand why their doctor ordered those labs 😊. Keeping the thyroid in check truly is a cornerstone of arrhythmia management.

Grover Walters

One might argue that the endocrine system serves as a silent orchestrator of cardiac tempo, a subtle conductor whose cues are often overlooked. In contemplating this symphony, the modest role of thyroid hormones emerges not as a villain but as a nuanced participant.

Amy Collins

Honestly, this whole thyroid‑arrhythmia thing is just another buzzword‑laden hype piece. The metabolic‑cardiac interplay is overblown; most patients just need a beta‑blocker, not a hormone deep‑dive.

amanda luize

What you call “buzzword‑laden hype” is precisely what the pharmaceutical lobby feeds us-an elaborate smokescreen to push thyroid‑modulating drugs while they hide the real agenda of cardiac control via covert nanotech. Stay alert; the truth is masked by glossy terminology.

Chris Morgan

While the article tries to sound comprehensive, it completely ignores the fact that most arrhythmias are independent of thyroid status. The focus on hormones is a distraction from more relevant risk factors.

Pallavi G

Actually, numerous studies have shown a statistically significant association between hyperthyroidism and atrial fibrillation, so thyroid screening isn’t a distraction-it’s a vital component of a holistic assessment. Let’s keep the conversation evidence‑based and supportive.

Rafael Lopez

To add to Pallavi’s point, the 2022 ATA guidelines recommend TSH testing for all patients presenting with new‑onset AF; the recommendation is graded Class I, Level A, indicating strong evidence. Moreover, beta‑blockers can mitigate symptoms while definitive thyroid management proceeds. Regular monitoring of free T4 and T3 ensures that therapy remains on target and reduces recurrence rates.

Kelly Diglio

I understand how daunting it can feel when a thyroid diagnosis appears to complicate an existing heart condition. The interplay between hormonal balance and electrical conduction is complex, yet knowledge empowers patients to take proactive steps. Regular follow‑up with both endocrinology and cardiology ensures that treatment plans are synchronized. Lifestyle modifications, such as stress reduction and balanced nutrition, complement medical therapy and can improve overall outcomes. Remember that many individuals successfully manage both conditions with the right multidisciplinary approach.

Carmelita Smith

Thanks for the clear info-very helpful! 😊

Liam Davis

Thyroid dysfunction indeed exerts a profound influence on cardiac electrophysiology, a fact that is often underappreciated in routine practice.

Hyperthyroidism accelerates the sinus node, shortens the refractory period, and predisposes patients to atrial fibrillation, while hypothyroidism can lead to bradyarrhythmias and prolongation of the QT interval.

Consequently, a thorough evaluation of thyroid function should be incorporated early in the diagnostic work‑up of any unexplained rhythm disturbance.

The measurement of serum TSH, free T4, and, when indicated, free T3 provides a clear biochemical picture that guides subsequent therapeutic decisions.

In cases of overt hyperthyroidism, antithyroid medications or definitive therapies such as radioactive iodine or surgery often normalize heart rate within weeks.

Beta‑blockers serve as a valuable bridge, controlling tachycardia and reducing the risk of ventricular ectopy while endocrine treatment takes effect.

For hypothyroid patients, levothyroxine replacement restores metabolic rate and gradually improves conduction velocity, though careful dose titration is essential to avoid precipitating atrial flutter.

It is also critical to monitor electrolytes, particularly potassium and magnesium, because electrolyte imbalances can amplify arrhythmic risk in the setting of thyroid disease.

Lifestyle interventions, including regular aerobic exercise, adequate sleep, and stress management techniques, synergistically support both endocrine and cardiac health.

Patients should be educated about the signs of worsening arrhythmia, such as palpitations, dizziness, or syncope, and instructed to seek prompt medical attention if these occur.

Collaborative care involving endocrinologists, cardiologists, and primary care providers ensures that medication adjustments are coordinated and that overlapping side effects are minimized.

In the follow‑up period, repeat thyroid panels every three to six months are advisable until hormonal levels stabilize.

Simultaneously, periodic ECG or Holter monitoring can detect residual arrhythmias and assess the efficacy of the combined therapeutic strategy.

Importantly, adherence to medication regimens and follow‑up appointments correlates strongly with favorable outcomes, a point that cannot be overstated.

Emerging research suggests that genetic polymorphisms in thyroid hormone receptors may further modulate individual susceptibility to arrhythmias, highlighting an area for future investigation.

By integrating these evidence‑based practices, clinicians can effectively tame the dual threat of thyroid imbalance and cardiac rhythm disruption, ultimately improving patient quality of life 😊.