Before 1995, if you lived in India, Brazil, or South Africa, you could buy life-saving HIV drugs for a fraction of what they cost in the U.S. or Europe. That’s because those countries didn’t have to honor product patents on medicines. They could make their own versions using different manufacturing methods. Then came TRIPS - the Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights Agreement - and everything changed.

What TRIPS Did to Generic Drugs

TRIPS, created by the World Trade Organization in 1995, forced every member country - including low-income nations - to grant 20-year patents on medicines from the date of filing. Before TRIPS, only 23 of 102 developing countries protected pharmaceutical products. By 2010, that number jumped to 147. This wasn’t just a legal tweak. It was a complete overhaul of how medicines were made and sold.

The result? Prices for patented drugs soared. A 2001 JAMA study found that in many developing countries, the cost of patented medicines rose by over 200% after TRIPS kicked in. Cancer drugs in India went up 300-500% after the country switched from process patents to product patents in 2005. In South Africa, 40 pharmaceutical companies sued the government in 1998 for trying to import cheaper generics. The lawsuit was dropped only after global protests.

The Compulsory Licensing Loophole That Almost Wasn’t

TRIPS wasn’t completely closed off to public health needs. Article 31 lets governments issue compulsory licenses - meaning they can authorize a local company to make a generic version of a patented drug without the patent holder’s permission. But there’s a catch: the license must be used mostly for the domestic market. So if you’re a small African country with no drug factories, you can’t just import generics made in India, even if you’re facing an AIDS crisis.

This rule made TRIPS practically useless for countries without manufacturing capacity. The 2003 Doha Declaration tried to fix this by affirming that public health overrides patents. But the real fix came in 2005 with the so-called ‘Paragraph 6 Solution’ - a legal workaround allowing countries to import generics made under compulsory license from another country. Sounds simple, right? It wasn’t.

By 2016, only one shipment of malaria medicine had ever moved through this system. Canada and Rwanda were the only two countries to use it successfully. The paperwork was so complex, the legal risks so high, that most governments gave up. As one WHO official put it, ‘The system was designed to let you breathe - but it gave you a straw instead of a hose.’

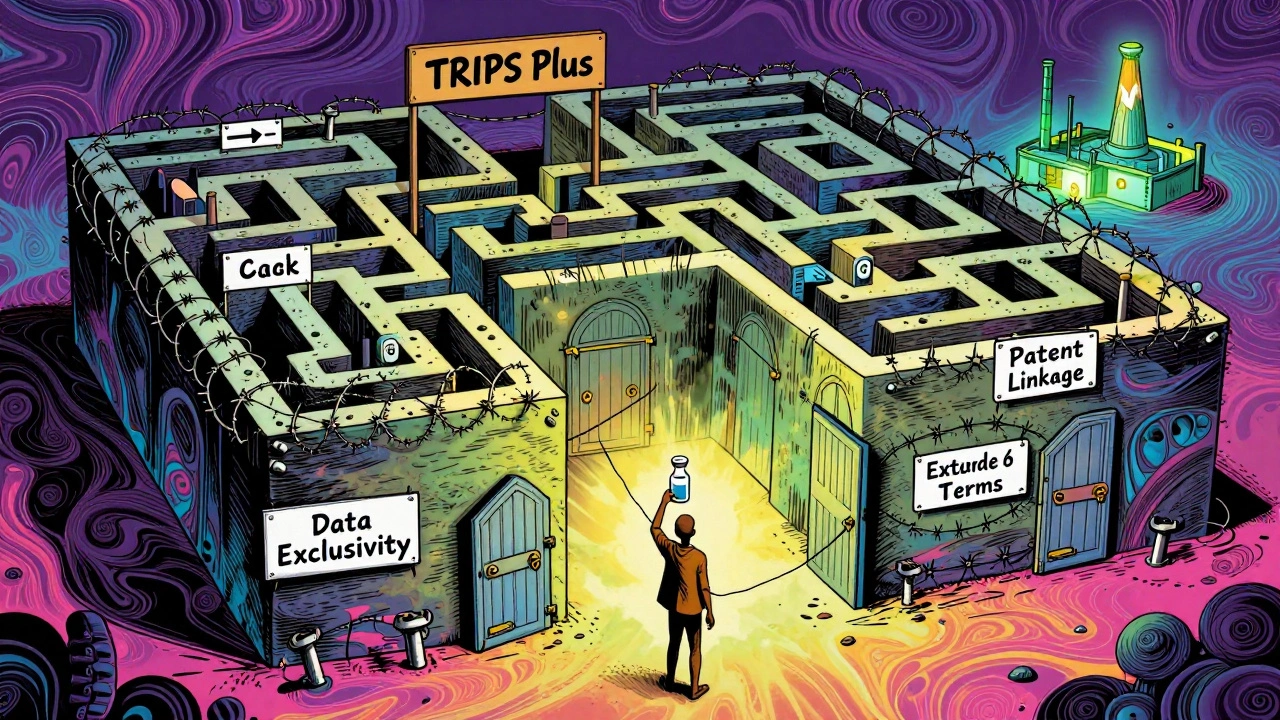

TRIPS Plus: The Hidden Rules That Hurt More

Even when countries followed TRIPS exactly, they still got hit with extra restrictions. These are called ‘TRIPS Plus’ rules - stricter patent rules pushed by wealthy nations through bilateral trade deals. The U.S. and EU started requiring developing countries to accept things TRIPS didn’t even mandate: extended patent terms beyond 20 years, data exclusivity (blocking generic makers from using originator clinical trial data for 5-10 years), and patent linkage (where drug regulators can’t approve generics until all patents are cleared, even if they’re invalid).

By 2020, 85% of U.S. free trade agreements included TRIPS Plus clauses. The EU-Vietnam deal, signed in 2020, gave eight years of data exclusivity - longer than TRIPS allows. The Access to Medicine Foundation found that 65% of low-income countries saw delays in generic approval because of these extra rules. These aren’t technicalities. They’re barriers that keep life-saving drugs off shelves for years longer than they should be.

Who Benefits? Who Pays?

Pharmaceutical companies argue that strong patents are needed to fund innovation. They point out that 73% of new medicines since 2000 came from companies in strong IP countries. But here’s the problem: most of those new drugs aren’t for the diseases that kill the most people in poor countries. Between 1975 and 1997, out of 1,223 new drugs approved, only 13 were for tropical diseases like malaria or sleeping sickness.

Meanwhile, the global generic medicine market hit $420.6 billion in 2020 - but almost all of that growth happened in rich countries. In low-income nations, 80% of medicines are off-patent, yet still out of reach because of patent barriers, high prices, and weak supply chains. The real success story? Antiretrovirals. Thanks to generic competition in places like India and Brazil, the cost of first-line HIV treatment dropped from $10,000 per patient per year in 2000 to just $75 in 2019. That’s not because of patents - it’s because of their absence.

The COVID-19 Waiver and What It Meant

In October 2020, India and South Africa proposed a temporary waiver of TRIPS protections for COVID-19 vaccines, tests, and treatments. Over 100 countries supported it. The U.S., EU, and Switzerland blocked it for over a year. When the WTO finally agreed in June 2022, the waiver was narrow: it only covered vaccines, not treatments or diagnostics, and only applied to countries with low vaccination rates. It also required complex notifications and didn’t touch data exclusivity or patent linkage.

It wasn’t a victory. It was a compromise that barely scratched the surface. The fact that it took two years to agree on something so basic showed how deeply entrenched the system is. The same companies that opposed the waiver are now pushing for patent extensions on new antiviral drugs like Paxlovid - meaning generic versions could be delayed for years.

The Real Cost of Delayed Generics

Every year a generic drug is blocked, people die. In 2021, the World Health Organization estimated that 1.3 million people in low-income countries couldn’t access HIV treatment because of patent barriers. In 2022, hepatitis C drugs priced at $84,000 per course in the U.S. were available in Egypt for $200 - thanks to local generic production. But in countries with strict TRIPS Plus rules, those same drugs remained unaffordable.

It’s not just about price. It’s about control. When a country can’t make its own medicines, it becomes dependent on foreign suppliers. A single shipment delay, a political dispute, or a corporate pricing decision can leave thousands without treatment. Countries like Thailand and Brazil managed to issue compulsory licenses for HIV drugs - but only after intense international pressure and legal battles.

What’s Next?

The Medicines Patent Pool, created in 2010, has helped bring down prices by negotiating voluntary licenses with drug makers. So far, it’s reached 17.4 million patients with HIV, hepatitis C, and TB drugs. But voluntary deals are not a solution - they’re a patch. Companies can refuse to license, change terms, or withdraw them at any time.

True change requires rewriting the rules. That means eliminating TRIPS Plus clauses, shortening data exclusivity, and making compulsory licensing simple and cross-border. It means recognizing that medicine isn’t a luxury product - it’s a public good. Until then, the system will keep working as designed: protecting profits, not people.

Does TRIPS ban generic drugs completely?

No, TRIPS doesn’t ban generics. It just makes them harder to produce. Countries can still issue compulsory licenses to make generic versions of patented drugs, but only under strict conditions - like proving they tried to get a voluntary license first and that the generics are mostly for domestic use. Many countries also face extra restrictions from trade deals (TRIPS Plus) that go beyond TRIPS rules.

Why can’t poor countries just import cheap generics from India?

Before 2005, they could - because India didn’t have product patents on drugs. But after TRIPS compliance, India started honoring those patents. Now, even if India makes a generic, other countries can’t legally import it unless they use the complicated ‘Paragraph 6 Solution,’ which requires both the exporting and importing country to issue compulsory licenses. Only a handful of shipments have ever gone through this system.

What’s the difference between a patent and data exclusivity?

A patent gives the drug maker exclusive rights to make and sell the medicine for 20 years. Data exclusivity is separate - it stops generic makers from using the original company’s clinical trial data to prove their version is safe and effective. Even after the patent expires, data exclusivity can delay generics by 5-10 years. This is not required by TRIPS, but many trade deals force it on developing countries.

Did TRIPS help innovation in developing countries?

Not really. While strong patents may encourage innovation in rich countries, there’s no evidence they’ve led to more drugs for diseases that affect poor nations. Between 1975 and 1997, only 13 of over 1,200 new drugs were for tropical diseases. Most pharmaceutical R&D focuses on chronic conditions in wealthy markets - not on malaria, TB, or cholera. TRIPS didn’t change that; it just made it harder for poor countries to access existing medicines.

Are there any countries that successfully used TRIPS flexibilities?

Yes - but only a few. Brazil issued compulsory licenses for HIV drugs in 2001 and 2007. Thailand did the same for cancer and heart drugs in 2006 and 2007. Both faced intense pressure from the U.S. and drug companies. South Africa tried in 1998 but was sued by 40 pharmaceutical firms. These cases show it’s possible - but politically risky and legally exhausting.

Christian Landry

bro this is wild. i had no idea patent rules could kill people like this. 😳

Maria Elisha

so basically pharma companies are holding life-saving meds hostage for profit? shocking. not.

Mona Schmidt

The structural inequities embedded in TRIPS aren't just legal-they're ethical failures disguised as trade policy. The fact that a child in Malawi can't access a $200 hepatitis C cure while the same drug costs $84,000 in the U.S. isn't a market outcome-it's a policy choice. Compulsory licensing exists on paper, but the bureaucratic labyrinth surrounding Paragraph 6 makes it functionally inaccessible. Data exclusivity, patent linkage, and TRIPS-Plus provisions aren't technicalities; they're deliberate obstructions. The Medicines Patent Pool is admirable, but voluntary licensing shouldn't be the ceiling of global health justice. Real reform requires dismantling the power imbalance that lets corporations dictate who lives and who dies based on geography.

Guylaine Lapointe

Oh please. If we didn't protect patents, no one would ever invest in new drugs. People forget that innovation doesn't happen in a vacuum. These companies spend billions-billions!-and you want them to just give it away? That's not fairness, that's theft. And now you're mad because the system works? Maybe stop blaming the medicine and start blaming the governments that can't distribute it properly.

Katie Harrison

It’s important to recognize that the TRIPS agreement was never intended to be a public health instrument-it was a trade instrument. And yet, we’ve allowed it to become the de facto global health policy. The ‘Paragraph 6 Solution’ was a band-aid on a hemorrhage. The fact that only one shipment of malaria medicine ever moved through it? That’s not a failure of implementation-it’s a failure of political will. Countries like Brazil and Thailand proved that compulsory licensing works. But they paid a price: diplomatic isolation, trade threats, and corporate smear campaigns. The real villain isn’t the patent law-it’s the coercion behind it. And until we stop treating medicine like a commodity, we’ll keep burying people under fine print.

Tejas Bubane

India made generics because it was poor and desperate not because it was smart. Now that we’re rich we’re playing by the rules. Why should we be punished for growing up? You want cheap drugs? Then build your own factories. Stop whining about patents like they’re a conspiracy. The West didn’t steal our tech-we just got outplayed. And now you want us to go back to being the pharmacy of the poor? No thanks.

Ajit Kumar Singh

TRIPS is a colonial tool wrapped in legal jargon. The U.S. and EU forced it down our throats in exchange for market access. We didn’t choose this-we were blackmailed. And now you wonder why no one uses the ‘Paragraph 6 Solution’? Because the paperwork alone costs more than the medicine. And the moment you try to use it, you get a phone call from Washington. Brazil and Thailand had to fight wars to make generics. We’re not supposed to win. We’re supposed to be grateful for scraps.

Elliot Barrett

So what? If you can't afford the drug, don't take it. Life isn't fair. The market decides who gets what. Stop pretending medicine is a human right-it's a product. And if you want it cheap, stop expecting someone else to pay for your healthcare.

Angela R. Cartes

OMG I just realized… the whole system is rigged. 😭 Like, how is this even legal? People are dying because of contracts? I’m so mad right now. Also, why is Canada still in this? We’re supposed to be nice??