Ranitidine Withdrawal Tracker

Withdrawal Timeline Calculator

Your Current Withdrawal Phase

Symptom Observations

Recommended Coping Strategies

When Ranitidine is taken off the market, many people wonder what will happen to their bodies. Ranitidine is an H2‑receptor antagonist that reduces stomach acid and was sold under brand names like Zantac. Zantac became the focus of worldwide recalls after the FDA found that some batches contained a probable carcinogen called NDMA. If you’ve been using ranitidine for heartburn, ulcers, or GERD, you might notice new aches, cravings for antacids, or even anxiety. This guide walks you through what to expect, how long symptoms usually last, and practical ways to cope.

Key Takeaways

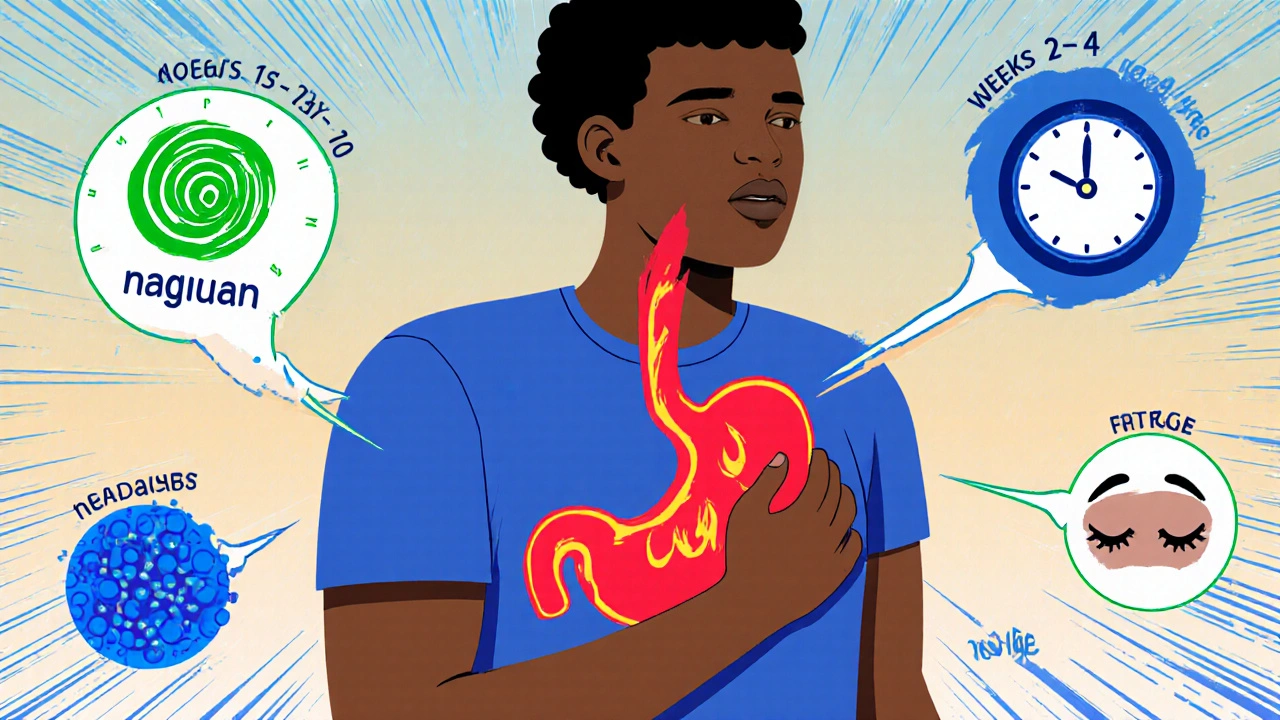

- Withdrawal symptoms usually start within a few days and fade in 2‑4 weeks for most people.

- Common signs include rebound acid reflux, nausea, headache, and sleep disturbances.

- Switching to a different H2 blocker (like famotidine) or a proton pump inhibitor can ease the transition.

- Lifestyle tweaks-diet, hydration, stress‑reduction-play a big role in managing discomfort.

- Seek medical help if symptoms worsen or you develop severe chest pain, vomiting blood, or unexplained weight loss.

Why a Withdrawal Happens

Ranitidine works by blocking histamine‑1 receptors in the stomach lining. Over weeks or months, your body adjusts to the lowered acid level. When the drug disappears, the stomach tries to compensate, often producing a surge of acid that feels like a flare‑up of the original condition. This rebound effect is what most people describe as “withdrawal.” It isn’t a classic drug‑dependence syndrome, but the sudden change can be uncomfortable.

The FDA’s 2020-2022 safety review discovered low‑level NDMA in some ranitidine lots, prompting a global pull‑back. While the chemical risk itself is minimal for short‑term users, the market exit created a sudden gap for millions of long‑term patients.

Typical Symptoms and Their Frequency

Based on surveys from gastroenterology clinics in Australia, the United Kingdom, and the United States, about 60% of former ranitidine users report at least one withdrawal symptom. Below are the most frequent issues:

- Rebound heartburn or acid reflux - 45% experience stronger burning sensations.

- Nausea or mild stomach upset - 30%.

- Headache - 25%.

- Fatigue or trouble sleeping - 20%.

- General anxiety or irritability - 15%.

Most symptoms are mild to moderate; severe complications are rare but can include ulcer flare‑ups or esophageal irritation.

Timeline: How Long Do Symptoms Last?

Everyone’s timeline differs, but a typical pattern looks like this:

- Days 1‑3: Initial acid surge, noticeable heartburn.

- Days 4‑10: Peak symptom intensity; nausea and headaches may appear.

- Weeks 2‑4: Gradual reduction; most people feel back to baseline.

- Weeks 4‑8: Residual discomfort for a minority; lifestyle changes become crucial.

If you’re still uncomfortable after eight weeks, it’s worth revisiting your doctor to rule out other gastrointestinal issues.

How to Cope: Medical Strategies

Below are steps you can take right away, many of which can be discussed with a pharmacist or GP.

- Switch to another H2 blocker: Famotidine (Pepcid) offers similar acid control without the NDMA concern. Start with the standard 20 mg dose twice daily and adjust under doctor guidance.

- Consider a proton pump inhibitor (PPI): If heartburn persists, a short course of omeprazole 20 mg daily for 2‑4 weeks can provide stronger suppression.

- Use antacids strategically: Over‑the‑counter options like calcium carbonate can relieve occasional spikes, but avoid excessive daily use.

- Talk to your GP about H2‑blocker tapering: While abrupt stop is common after a recall, a slow reduction (e.g., half dose for a week) can blunt rebound acid.

Remember, any medication change should be documented, especially if you have chronic conditions such as diabetes or heart disease, because acid‑reducing drugs can affect drug absorption.

Lifestyle Tweaks That Help

Even without prescription changes, daily habits can cut down withdrawal misery.

- Eat smaller, frequent meals: Large meals stimulate acid production.

- Avoid trigger foods: Spicy dishes, citrus, caffeine, and chocolate are common culprits.

- Stay upright after eating: Wait at least 2‑3 hours before lying down.

- Hydrate wisely: Sip water throughout the day but limit large amounts during meals.

- Manage stress: Techniques like deep‑breathing, yoga, or short walks can reduce stomach‑acid spikes caused by anxiety.

Tracking your symptoms in a simple notebook-note timing, food, and relief methods-helps you spot patterns and discuss them with your clinician.

Alternative Medications After Ranitidine

Below is a quick comparison of the most common acid‑control drugs you might consider once you’re off ranitidine.

| Drug | Class | Typical Dose | Onset (hrs) | Common Side Effects |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Famotidine | H2‑receptor antagonist | 20 mg BID | 0.5‑1 | Headache, dizziness |

| Omeprazole | Proton pump inhibitor | 20 mg daily | 1‑3 | Diarrhoea, flatulence |

| Lansoprazole | PPI | 15 mg daily | 1‑2 | Headache, nausea |

| Antacids (Calcium carbonate) | Neutralising agent | as needed | Immediate | Gas, constipation |

Each option has pros and cons. PPIs provide stronger, longer‑lasting suppression but may interfere with magnesium absorption over time. H2 blockers like famotidine are gentler and work well for most people transitioning from ranitidine.

When to Seek Professional Help

Most patients navigate the withdrawal period at home, but certain red flags mean you should call your GP or head to the emergency department:

- Severe chest pain that doesn’t improve with antacids.

- Vomiting blood or material that looks like coffee grounds.

- Unexplained weight loss exceeding 5 % of body weight.

- Persistent fever or signs of infection.

In these cases, prompt evaluation can rule out ulcer perforation or other serious complications.

What to Expect After the First Month

Most people notice a steady decline in heartburn intensity after four weeks. Your stomach lining may have adapted to produce less acid on its own, especially if you’ve adopted the lifestyle habits above. It’s common to feel a “new normal” where occasional mild reflux occurs but doesn’t dominate your day.

If you continue to need medication after three months, discuss a long‑term plan with your doctor. Chronic reflux may require ongoing PPI therapy, but many clinicians aim for the lowest effective dose to minimise side‑effects.

Quick FAQ

How soon after stopping ranitidine do symptoms appear?

Most users feel the first signs of rebound acid within 24‑48 hours, though some people notice changes a bit later.

Can I take antacids while withdrawing?

Yes, occasional antacids can relieve spikes, but avoid using them every day for weeks without doctor advice.

Is famotidine a safe replacement?

Famotidine is the most commonly suggested H2 blocker after ranitidine. It has a good safety record and doesn’t contain NDMA.

What lifestyle changes help the most?

Eating smaller meals, avoiding trigger foods, staying upright after eating, and managing stress are the top three habits that cut rebound symptoms.

When should I call my doctor?

If you experience severe chest pain, vomiting blood, rapid weight loss, or symptoms that last beyond eight weeks, seek medical attention promptly.

If you’re navigating a sudden stop to ranitidine, remember you’re not alone. By recognizing the typical timeline, using the right substitutes, and tweaking daily habits, you can get through the withdrawal period with minimal disruption. Should symptoms linger or worsen, a quick chat with your GP will keep you on the right track.

Michaela Dixon

The sudden disappearance of ranitidine felt like the lights went out on a familiar street. Your stomach, accustomed to a lowered acid tide, suddenly floods with a wave of hydrochloric fire. This rebound surge can turn a mild after‑dinner discomfort into a full‑blown torrent of heartburn. Many people report that the first days are the most chaotic as the body scrambles to find a new equilibrium. The guide rightly points out that symptoms usually ease after two to four weeks for the majority. If you keep a notebook, you will notice patterns that help you predict when the worst moments hit. Small, frequent meals act like a dam, slowing the rush of acid into the esophagus. Avoiding spicy sauces, caffeine, and chocolate can keep the fire from flaring too high. Staying upright after eating is a simple trick that prevents gravity from pushing acid upward. Hydration, especially sipping water between bites, dilutes the acidity without overloading the stomach. Some users find that a brief trial of famotidine smooths the transition because it still blocks H2 receptors without the NDMA worry. Others prefer a short course of a proton pump inhibitor, which shuts down acid production more aggressively. Remember that PPIs may interfere with magnesium and vitamin B12 absorption if used for months on end. Stress management, through breathing exercises or short walks, reduces the hormone signals that tell the stomach to produce more acid. If pain becomes severe, chest tightness emerges, or you see blood, call a doctor without delay. In the end, the body is resilient and will usually settle into a new normal once you give it the right tools and patience.

Dan Danuts

Hey, that’s spot on – the rebound can feel like a volcano erupting, but you’ve got the right game plan! Keep tracking those meals and you’ll see the spikes drop faster than you think. If you feel a little extra fire, a chewable antacid can be a quick rescue while your new meds settle in. Stay positive and remember the body loves consistency, so stick to those small meals and you’ll be back cruising in no time!

Dante Russello

Absolutely, Dan, the key is consistency, and you’ve nailed that point; maintaining a food diary, for example, provides invaluable data, allowing you to spot triggers before they flare up. Moreover, integrating a gentle probiotic, such as Lactobacillus acidophilus, can help balance gut flora, which, in turn, may modulate acid production. Don’t forget to schedule short, mindful breathing sessions after meals – they calm the vagus nerve, reducing unnecessary acid secretion. If you decide to switch to famotidine, start with the recommended dose, monitor your response, and adjust under medical guidance. Lastly, keep hydrated, but avoid gulping large volumes during meals; sip slowly throughout the day to keep the stomach environment stable.

James Gray

Yo, great tips! I tried the small meal trick and it actually made a big difference – no more midnight burn. I also swapped to Pepcid and the rebound was way less intense, so shoutout to famotidine for saving my night. Keep it up, we all got this!

Scott Ring

Reading through all the advice, I’m reminded how many of us share the same stomach saga, regardless of where we grew up. In my experience, adding a dash of turmeric to meals has a soothing effect, and pairing it with a short walk after dinner can keep the reflux at bay. It’s also helpful to chat with a pharmacist about tapering; they often have simple dose‑reduction schedules that make the transition smoother. Remember, you’re not alone in this – community tips and professional guidance together can turn the withdrawal into a manageable chapter.

Shubhi Sahni

Scott, you hit the nail on the head; cultural dietary practices, such as using ginger or fennel, often provide natural relief, and sharing these insights enriches the whole community. Additionally, keeping a symptom‑log with timestamps, food items, and relief measures can be invaluable when discussing progress with your GP, enabling a data‑driven approach. It’s also worth noting that stress‑reduction techniques, like progressive muscle relaxation, have been shown to lower gastric acid output, complementing any pharmacologic strategy. Together, these small but consistent actions build a robust defense against rebound discomfort.

Danielle St. Marie

Only real Americans trust proven meds, not foreign recalls 🙄🇺🇸.

keerthi yeligay

Those claims ignore the science, many folks worldwide benefit safe from ranitidine alternatives.