When you’re pregnant, every decision feels heavier. That headache? Should you take acetaminophen? What about that anxiety medication you’ve been on for years? The fear isn’t irrational - it’s grounded in real science. About 2-3% of all birth defects are linked to medications taken during pregnancy. That number might sound small, but for the families affected, it’s everything.

What Exactly Is a Teratogen?

A teratogen is any substance - drug, chemical, or even infection - that can interfere with fetal development and cause structural or functional abnormalities. The term comes from the Greek word teras, meaning monster. It’s a harsh word, but the history behind it is even harsher.

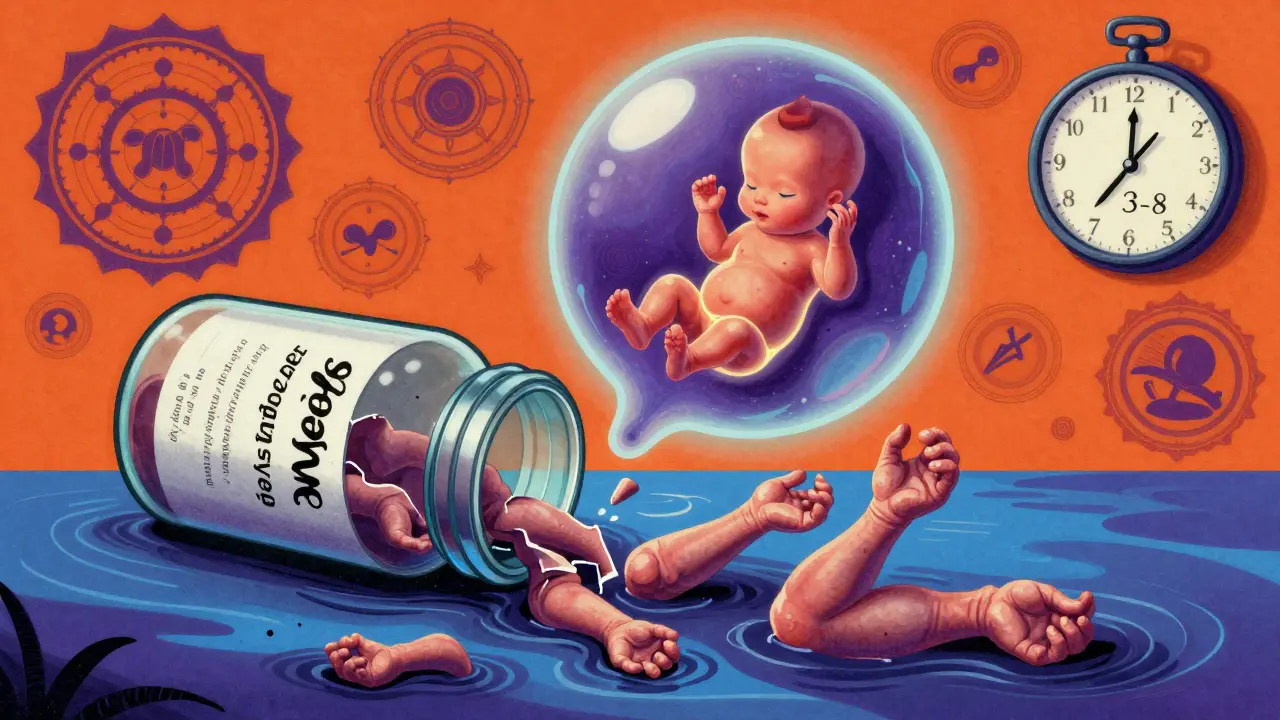

In the late 1950s, thalidomide was sold as a safe sleep aid and morning sickness remedy across Europe, Canada, and Australia. By 1961, more than 10,000 babies were born with missing or malformed limbs. Some had no arms. Others had hands growing directly from their shoulders. The world learned a brutal lesson: what’s safe for a mother isn’t always safe for the baby. That tragedy changed how we test drugs forever.

When Does the Risk Happen?

Not all stages of pregnancy carry the same risk. The first trimester - especially between weeks 3 and 8 after conception - is when the baby’s organs are forming. That’s the most sensitive window. A medication taken during this time can cause major structural problems like heart defects, cleft lip, or missing limbs.

By the second trimester, the big structures are mostly done. But the brain, eyes, and genitals are still developing. This is when medications might cause functional issues - like hearing loss, learning delays, or eye abnormalities. In the third trimester, drugs mostly affect how organs work. For example, some antidepressants can cause temporary withdrawal symptoms in newborns. Others can trigger early labor or low birth weight.

Here’s the thing: 60-70% of medications you take during pregnancy have no effect at all on the baby. But you can’t assume safety. You need to know which ones are risky.

Medications With Known Risks

Some drugs have clear, well-documented dangers:

- Warfarin (a blood thinner): Can cause fetal warfarin syndrome - a pattern of facial deformities, bone problems, vision loss, and intellectual disability. Risk is highest in the first trimester.

- Carbamazepine (for epilepsy): Increases neural tube defect risk by about 1%. Also reduces vitamin K, which can lead to dangerous bleeding in newborns.

- Methotrexate (used for autoimmune diseases and cancer): A folate blocker. Even a single dose in early pregnancy can cause severe defects, including missing skull bones and limb problems. Risk jumps to 10-20% for neural tube defects.

- Factor Xa inhibitors (rivaroxaban, apixaban): These newer blood thinners cross the placenta. There’s no antidote if bleeding happens. No one knows how safe they are. Avoid them.

- Cannabis (THC): Studies show a 15-20% higher chance of low birth weight, 10-15% higher risk of preterm birth, and possible stillbirth. THC stays in breastmilk for days. Babies exposed may be more hyperactive and have trouble focusing later on.

These aren’t rare cases. They’re documented patterns. If you’re taking any of these, talk to your provider - don’t stop cold turkey without a plan.

The Acetaminophen Controversy

Acetaminophen (Tylenol, paracetamol) is the go-to painkiller for pregnant women. It’s been used for decades. But now, some studies are raising red flags.

The CDC says some research links long-term acetaminophen use during pregnancy to higher rates of ADHD and autism. But they’re careful to say: no proven cause. Meanwhile, ACOG (the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists) released a strong statement in September 2025: acetaminophen is safe and necessary. Why? Because untreated fever during pregnancy carries a 20-30% higher risk of neural tube defects. Untreated pain? That can raise blood pressure, trigger stress hormones, and even lead to preterm labor.

So what’s the truth? The risks of not treating pain or fever are far greater than the possible, unproven risks of acetaminophen. ACOG’s message is clear: use it when needed. Don’t avoid it out of fear. But don’t take it daily for no reason, either. Use the lowest dose for the shortest time.

Why So Much Confusion?

Most pregnant women are bombarded with conflicting advice. Reddit threads, Facebook groups, Pinterest infographics - they’re full of fear, not facts. One woman in Seattle wrote: “My OB said Zofran was fine for nausea. Then I read it might cause cleft palate. I cried for three days.”

Here’s why this happens:

- Only about 20% of medications have solid data on pregnancy safety.

- The FDA got rid of the old A-B-C-D-X letter system in 2015. Now labels give detailed narratives. But most people still look for a simple “safe” or “dangerous” label.

- Online sources often misinterpret animal studies or small case reports as proof of harm.

- Most pregnancy safety data comes from watching what happens after the fact - not from controlled trials. That means we’re piecing together clues, not proving causes.

And here’s the biggest gap: 95% of what we know comes from observational studies. We can’t ethically give drugs to pregnant women in a lab and see what happens. So we watch. We record. We guess. And sometimes, we’re wrong.

What Should You Do?

You don’t need to panic. You need a plan.

- Review all medications before you get pregnant. Even if you’re not trying, use birth control if you’re on a high-risk drug. Many pregnancies are unplanned - 40-50% of them.

- Don’t stop medications on your own. Stopping seizure meds, blood pressure drugs, or antidepressants can be more dangerous than the drug itself. ACOG says: “Sometimes, not taking a medicine is riskier than taking it.”

- Use trusted resources. MotherToBaby (a free service run by experts) handles over 10,000 calls a year. LactMed and the FDA’s drug database are reliable. Avoid blogs.

- Talk to a pharmacist. Pharmacists are medication experts. They know interactions, dosing, and alternatives. ACOG says consulting one is “prudent.”

- Ask about alternatives. Is there a non-drug option? Heat packs for back pain? Acupuncture for nausea? Sometimes, yes.

And if you’ve already taken something risky? Don’t panic. Most exposures don’t lead to defects. Call MotherToBaby. Get a risk assessment. They’ll tell you what’s likely, what’s unlikely, and what to watch for.

The Bigger Picture

Only 2-3% of maternal health research funding goes to medication safety. That’s shocking when you consider how many women take at least one drug during pregnancy. The FDA is trying to fix this. They’re expanding the Sentinel Initiative - tracking 10 million patient records by 2026 to find real-world patterns.

Experts predict that in five years, we’ll be able to predict individual risk using genetics. Some women metabolize drugs differently. Their babies might be more or less vulnerable. That’s the future.

Right now, we’re stuck with what we have: incomplete data, conflicting advice, and a lot of fear. But you’re not alone. Millions of women have taken medications during pregnancy and had healthy babies. The key isn’t perfection - it’s awareness. And knowing when to ask for help.

Can I take ibuprofen while pregnant?

Avoid ibuprofen after 20 weeks of pregnancy. It can reduce amniotic fluid and affect the baby’s heart. Before 20 weeks, occasional use is usually okay, but acetaminophen is still the safer choice. Always check with your provider.

Is it safe to take antidepressants during pregnancy?

Untreated depression can raise the risk of preterm birth, low birth weight, and postpartum complications. For many women, the benefits of continuing antidepressants like sertraline or citalopram outweigh the risks. These are among the best-studied options. Never stop abruptly - work with your doctor to adjust safely.

What if I took a medication before I knew I was pregnant?

Most exposures don’t cause harm. The baby’s development depends on timing, dose, and the specific drug. If you took a medication in the first few weeks - before you missed your period - it’s often an “all or nothing” scenario: either it affected the pregnancy enough to cause a miscarriage, or it didn’t affect it at all. Call MotherToBaby or your provider for personalized advice.

Are herbal supplements safe during pregnancy?

No. Herbal products aren’t regulated like drugs. Many contain active ingredients that can cause contractions, affect hormone levels, or interfere with fetal development. Ginger is generally safe for nausea, but others - like black cohosh, goldenseal, or high-dose vitamin A - can be dangerous. Always check with your provider before taking anything labeled “natural.”

Where can I get reliable information about my medication?

Use trusted sources: MotherToBaby (1-800-973-4911), LactMed (from the National Library of Medicine), the FDA’s pregnancy labeling on prescription inserts, and your pharmacist. Avoid Google searches, forums, or Instagram posts. If it’s not from a medical institution, it’s not reliable.

What’s Next?

If you’re planning pregnancy, schedule a preconception visit. Bring your pill bottles. Ask: “What should I stop? What should I keep? What’s the safest option?” If you’re already pregnant and unsure about a medication, don’t wait. Call your provider today. You don’t need to carry this fear alone. The tools, the experts, and the data are there - you just need to ask for them.

PAUL MCQUEEN

I read the whole thing. Honestly? The article is way too long. They could’ve just said: 'Don’t take anything unless your doctor says so.' Why the 2000-word lecture? I’m not a med student. Just give me the TL;DR.

Kathryn Lenn

Oh wow, so now acetaminophen is 'safe'... until the next study says it causes autism, right? And let’s not forget how 'safe' thalidomide was too. Funny how these 'trusted experts' always seem to get it wrong... until the babies are born. I’m not taking a chance. If it’s not FDA-approved for pregnancy, I’m not touching it. Period. 🤷♀️

Tasha Lake

The pharmacokinetics of placental transfer are fascinating-especially how lipid-soluble compounds like THC and SSRIs cross the blood-placental barrier via passive diffusion. But what’s rarely discussed is inter-individual variability in CYP450 enzyme expression. Some women are ultra-rapid metabolizers; their fetuses get exposed to higher concentrations of active metabolites. That’s why population-level data is so misleading. We need personalized teratogenic risk modeling.

Simon Critchley

I’ve been a pharmacist in London for 18 years. Let me tell you-most of these 'risks' are blown out of proportion. I’ve had 37 pregnant patients on sertraline. All had healthy babies. The real danger? Anxiety. Stress. Not taking meds because some Reddit post scared them. You’re more likely to miscarry from panic than from Tylenol. Chill. Talk to your GP. Don’t Google.

John McDonald

I’m a dad. My wife took Zofran, prenatal vitamins, and 3 doses of Advil before she knew she was pregnant. Baby’s 2 now, hitting every milestone. The fear is real-but so is the fact that 97% of women who take meds during pregnancy have healthy kids. You’re not a lab rat. You’re a person. Trust your doc. Don’t let fear run your life.

Tori Thenazi

Wait... so if I took ibuprofen at 18 weeks... does that mean my daughter’s ADHD is from that? And what about the 5mg melatonin I took for insomnia? And the chamomile tea? And the essential oils? Oh my god... I’m going to be the mom who ruined her child’s life. I’m crying. I’m so sorry. I didn’t know. I didn’t know. I didn’t know. 😭😭😭

John Watts

You’re not alone. Seriously. I’ve talked to hundreds of moms in my work as a doula. Every single one of them has been terrified. But here’s the truth: your body is designed to protect your baby. And your doctor is there to help-not to judge. You’re not failing. You’re learning. You’re doing better than you think. One step at a time. You’ve got this.

glenn mendoza

It is imperative to underscore the significance of evidence-based clinical guidance in maternal pharmacotherapy. The conflation of anecdotal narratives with empirical data has precipitated a public health crisis of misinformation. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, in conjunction with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, maintains a rigorous, peer-reviewed framework for evaluating teratogenic risk. It is incumbent upon all expectant individuals to consult authoritative sources prior to altering pharmacological regimens.

Chelsea Deflyss

i just took one advil last week and now im terrified. what if my baby has no arms? i cant sleep. i think i need to go to the hospital. maybe they can scan the baby? or is it too late? i dont even know what week it is anymore. someone please help me. i just wanted to stop my headache.

Ryan Vargas

The entire paradigm of prenatal pharmacology is built on a foundation of observational bias and ethical constraints. We have no RCTs because we can’t ethically administer drugs to pregnant women. So we rely on registries, case reports, and post-marketing surveillance-all inherently flawed. The 2-3% birth defect statistic? It’s a statistical mirage. We’re attributing anomalies to drugs because we have no other framework. What if environmental toxins, epigenetic shifts, or maternal stress are the real drivers? We’re scapegoating medications because it’s easier than confronting systemic healthcare failure.

Susan Kwan

You say 'talk to your provider.' But what if your provider doesn’t know? I asked my OB about Zofran. She said 'it’s fine.' Then I asked a pharmacist. He said 'avoid it.' Then I called MotherToBaby. They said 'it’s low risk but monitor.' So now I’m confused. Who do I trust? The system is broken. And no, I’m not going to Google it. I’ve already lost sleep over this.

Randy Harkins

I just wanted to say thank you for writing this. 🙏 I was so scared after taking one dose of ibuprofen before I knew I was pregnant. I cried for days. But reading this made me feel like I’m not a monster. I’m just trying to be a good mom. And sometimes, that means taking meds. You’re right-we need more research. But we also need more compassion. You helped me today.

Monica Warnick

I took a single dose of melatonin at 5 weeks. I didn’t know it was pregnancy. Now I’m 16 weeks. I’m not going to tell anyone. I don’t want to be judged. I don’t want to be one of those 'bad moms.' I just want my baby to be okay.